|

|

AbstractPurposeTo study the performance of the combined models of Pediatric Risk of Admission (PRISA) scores I and II and C-reactive protein (CRP) for prediction of hospitalization in febrile children who visited the emergency department.

MethodsWe reviewed febrile children aged 4 months - 17 years who visited a tertiary hospital emergency department between January and December 2017. White blood cell count, CRP concentration, the PRISA scores, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome score were calculated. We compared areas under the curves (AUCs) of the admission decision support tools for hospitalization using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

ResultsOf 1,032 enrolled children, 423 (41.0%) were hospitalized. CRP and the PRISA scores were significantly higher in the hospitalization group than in the discharge group (all P < 0.001). Among the individual tools, CRP showed the highest AUC (0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66-0.72). AUC was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.69-0.74) for the combined model of the PRISA I score and CRP, and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.68-0.74) for that of the PRISA II score and CRP. The AUC of PRISA score I and CRP combined was significantly higher than that of isolated CRP (P=0.048).

žĄúŽ°†žóīžĚÄ žĚĎÍłČŪôėžěźžĚė žēĹ 31%Ž•ľ žį®žßÄŪēėŽäĒ žÜĆžēĄ žĚĎÍłČŪôėžěźžĚė ŪĚĒŪēú žĚĎÍłČžč§ Žį©Ž¨ł žĚīžú† ž§Ď ŪēėŽāėžĚīŽč§[1,2]. žēĹ 20%žĚė žÜĆžēĄÍįÄ žóīžĚĄ ž£ľžÜĆŽ°ú Žį©Ž¨łŪēėŽäĒŽćį, žĚī ž§Ď žēĹ 26%ÍįÄ žěÖžõźŪēėžßÄŽßĆ[3] Í∑ł Íłįž§ÄžĚī ž£ľÍīÄž†ĀžĚł Í≤ÉžĚī ŪėĄžč§žĚīŽč§. žěÖžõź Íłįž§ÄžĚė ž£ľÍīÄž†ĀžĚł Ž©īžĚĄ Ž≥īžôĄŪēėŽ†§Ž©ī, ÍįĚÍīÄž†Ā žěÖžõź žėąžł° ŽŹĄÍĶ¨ÍįÄ ŪēĄžöĒŪēėŽč§. Pediatric Risk of Admission (PRISA) ž†źžąė I ŽįŹ IIŽäĒ ŪėĄŽ≥ĎŽ†•, Í≥ľÍĪįŽ†•, žč†ž≤īÍ≤Äžā¨, Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨, žĚĎͳȞ≤ėžĻėžóź ÍłįŽįėŪēėžó¨ žÜĆžēĄŪôėžěź žěÖžõźžĚĄ žėąžł°ŪēėŽäĒ ž†źžąė ž≤īÍ≥ĄžĚīŽč§(Appendix 1) [3-5]. žóī ŪôėžěźžóźÍ≤Ć ŪĚĒŪěą žčúŪĖČŪēėŽäĒ žóľž¶ĚŪĎúžßĞ쟞̳ C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚÄ serious bacterial infection (SBI) žėąžł°žĚĄ ŪÜĶŪēī žěÖžõź žėąžł°žóź ŽŹĄžõĞ̥ ž§ÄŽč§[6-10]. ŪēúÍĶ≠žóźžĄú žĚīŽü¨Ūēú ŽŹĄÍĶ¨Ž•ľ žĚīžö©Ūēú žěÖžõź žėąžł° žóįÍĶ¨ÍįÄ Ž∂Äž°ĪŪēú žč§ž†ēžĚīŽč§.

Ž≥ł ž†ÄžěźŽäĒ žóī ŪôėžěźžóźžĄú PRISA ž†źžąė Žč®ŽŹÖ ŽįŹ žó¨Íłįžóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēžĚė žěÖžõź žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ ŪŹČÍįÄŪēėÍ≥†žěź Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨Ž•ľ žąėŪĖČŪĖąŽč§.

ŽĆÄžÉĀÍ≥ľ Žį©Ž≤ē1. žóįÍĶ¨ŽĆÄžÉĀ2017ŽÖĄ 1žõĒŽ∂ÄŪĄį 12žõĒÍĻĆžßÄ Í≤ĹžÉĀŽĆÄŪēôÍĶźŽ≥Ďžõź žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ Žį©Ž¨łŪēú 4ÍįúžõĒ-17žĄł žóī ŪôėžěźŽ•ľ ŽĆÄžÉĀžúľŽ°ú žčúŪĖČŪĖąŽč§. Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨ ŽėźŽäĒ žĚėŽ¨īÍłįŽ°Ě ŽąĄŽĚĹžúľŽ°ú PRISA I, II, ž†Ąžč†žóľž¶ĚŽįėžĚĎž¶ĚŪõĄÍĶį ž†źžąė, C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßą, ŽįĪŪėąÍĶ¨Í≥Ąžāį ŽďĪžĚė Í≤įÍ≥ľŽ•ľ žĖĽžĚĄ žąė žóÜŽäĒ ŪôėžěźŽäĒ ž†úžôłŪĖąŽč§. Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨ŽäĒ Í≤ĹžÉĀŽĆÄŪēôÍĶźŽ≥Ďžõź žěĄžÉĀžóįÍĶ¨žč¨žĚėžúĄžõźŪöĆ žäĻžĚłžĚĄ žĖĽžĚÄ ŪõĄ žčúŪĖČŪĖąŽč§(IRB No. GNUH 2019-02-006).

2. žěźŽ£ĆžąėžßĎÍįĀ žßÄŪĎúŽ•ľ žāįž∂úŪēėÍłį žúĄŪēėžó¨ ž†ĄžěźžĚėŽ¨īÍłįŽ°ĚžĚĄ žĚīžö©Ūēėžó¨ ŪõĄŪĖ•ž†ĀžúľŽ°ú žěźŽ£ĆŽ•ľ žąėžßĎŪĖąŽč§. žąėžßĎŪēú žěźŽ£ĆŽäĒ žĚĎÍłČžč§ Žį©Ž¨ł Žį©Ž≤ē, ŽāėžĚī, žĄĪŽ≥Ą, Í≥ľÍĪįŽ†•, Ūėąžēē, žč¨žě• ŽįēŽŹôžąė, ŪėłŪĚ°žąė, ž≤īžė®, žč†ž≤īÍ≤Äžā¨ Í≤įÍ≥ľ, Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨ Í≤įÍ≥ľ(ŪŹ¨ŽŹĄŽčĻ, ŽįĪŪėąÍĶ¨Í≥Ąžāį, Ū󧎙®ÍłÄŽ°úŽĻą ŽÜ掏Ą, ŪėąžÜĆŪĆźÍ≥Ąžāį, ž§ĎŪÉĄžāįžĚīžė® ŽÜ掏Ą, Ūėąžē°žöĒžÜĆžßąžÜĆ, C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßą, žĻľŽ•®), žĚĎͳȞ≤ėžĻė ŽįŹ žěÖžõź žó¨Ž∂Ä, žĚĎÍłČžč§ 7žĚľ žĚīŽāī žě¨Žį©Ž¨ł, žĚĎÍłČžč§ Žį©Ž¨ł 30žĚľ žĚīŽāī žā¨ŽßĚ, žßĄŽč®Ž™Ö(žóī žõźžĚł)žĚīŽč§. ŪôúŽ†•žßēŪõĄ, žč†ž≤īÍ≤Äžā¨, Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨ŽäĒ žĚĎÍłČžč§ Žį©Ž¨ł žīąÍłįžóź žčúŪĖČŪēú Í≤įÍ≥ľŽßƞ̥ Ž∂ĄžĄĚŪĖąŽč§.

3. ž†ēžĚėÍłįž°ī Ž¨łŪóĆžóź ŽĒįŽ•ł žóīžĚė ž†ēžĚė(žßĀžě• ž≤īžė® 38‚ĄÉ, Í≤®ŽďúŽěĎ ž≤īžė® 37.5‚ĄÉ ŽėźŽäĒ Í≥†ŽßČ ž≤īžė® 37.6‚ĄÉ žĚīžÉĀ)Ž•ľ žįłÍ≥†Ūēėžó¨[11,12], Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨žóźžĄú žóīžĚĄ Í≥†ŽßČ ž≤īžė® 37.6‚ĄÉ ŽėźŽäĒ žē°žôÄ ž≤īžė® 37.5‚ĄÉ žĚīžÉĀžúľŽ°ú ž†ēžĚėŪĖąŽč§[11,12]. žßĄŽč®Ž™ÖžĚÄ žěÖžõźÍĶįžĚÄ Ž≥ĎŽŹô Ūáīžõź žßĄŽč®Ž™ÖžĚĄ, ŪáīžõźÍĶįžĚÄ žĚĎÍłČžč§ Ūáīžč§ žßĄŽč®Ž™ÖžĚĄ ÍįĀÍįĀ žā¨žö©ŪĖąžúľŽ©į, ŽĎź ÍĶį Ž™®ŽĎź žÜĆžēĄž≤≠žÜĆŽÖĄÍ≥ľ žĚėžā¨ÍįÄ Í≤įž†ēŪēú žßĄŽč®Ž™ÖžĚĄ žā¨žö©ŪĖąŽč§.

4. žěÖžõź žėąžł° ŽŹĄÍĶ¨PRISA ž†źžąė I (Appendix 1)žĚÄ ŪėĄŽ≥ĎŽ†•, Í≥ľÍĪįŽ†•, žč†ž≤īÍ≤Äžā¨, Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨, žĚĎͳȞ≤ėžĻėžóź ÍłįŽįėŪēėžó¨ ÍĶźŽěÄŽ≥Äžąė 4žĘ̥֞ Ž≥īž†ēŪēėžó¨ žāįž∂úŪēėžßÄŽßĆ, žĚĎͳȞ觞󟞥ú žā¨žö©ŪēėÍłįžóź Žč§žÜĆ Ž≥Ķžě°ŪēėÍ≥† ŪÉÄŽčĻŽŹĄ Í≤Äž¶ĚžĚī Ž∂ąž∂©Ž∂ĄŪēėŽč§[4]. žĚīŽ•ľ Ž≥īžôĄŪēú PRISA ž†źžąė II (Appendix 2)ŽäĒ ŽĆÄÍ∑úŽ™® ŪôėžěźŽ•ľ ŽĆÄžÉĀžúľŽ°ú ŪÉÄŽčĻŽŹĄŽ•ľ Í≤Äž¶ĚŪĖąžúľŽ©į Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨ 4žĘ̥֞ ŪŹ¨Ūē®Ūēú žīĚ 16ÍįúžĚė Ž≥ÄžąėŽ•ľ žĚīžö©Ūēėžó¨ ž†źžąėŽ•ľ žāįž∂úŪēúŽč§. ŽĎź ŽŹĄÍĶ¨žĚė žěÖžõź žėąžł°žĄĪž†Āžóź žú†žĚėŪēú žį®žĚīŽäĒ žóÜŽč§Í≥† žēĆŽ†§ž°ĆŽč§(PRISA scores I vs. II; area under the curve [AUC] 0.83 ¬Ī 0.02 vs. AUC 0.77 ¬Ī 0.02)[5]. C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚÄ SBI žėąžł°žóź žú†žö©ŪēėŽč§. Lacour ŽďĪ6)žĚÄ žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ Žį©Ž¨łŪēú 36ÍįúžõĒ žĚīŪēėžĚė žóī ŪôėžěźžóźžĄú C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė SBIžóź ŽĆÄŪēú ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄžôÄ ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄŽ•ľ ÍįĀÍįĀ 89%žôÄ 75%Ž°ú Ž≥īÍ≥†ŪĖąŽč§.

5. ŪÜĶÍ≥Ąž†Ā Žį©Ž≤ēžóįžÜćŪėē Ž≥ÄžąėŽäĒ ž†ēÍ∑úŽ∂ĄŪŹ¨ žó¨Ž∂Äžóź ŽĒįŽĚľ ŪŹČÍ∑† ŽįŹ ŪĎúž§ÄŪéłžį® ŽėźŽäĒ ž§ĎžēôÍįí ŽįŹ žā¨Ž∂ĄžúĄžąė Ž≤ĒžúĄŽ°ú ŪĎúžčúŪĖąžúľŽ©į, Ž≤Ēž£ľŪėē Ž≥ÄžąėŽäĒ žąėžôÄ ŽįĪŽ∂Ąžú®Ž°ú Íłįžě¨ŪĖąŽč§. žóįžÜćŪėē Ž≥Äžąėžóź ŽĆÄŪēīžĄúŽäĒ Mann-Whitney U testŽ•ľ, Ž≤Ēž£ľŪėē Ž≥Äžąėžóź ŽĆÄŪēīžĄúŽäĒ chi-square test ŽėźŽäĒ Fisher exact testŽ•ľ ÍįĀÍįĀ žā¨žö©ŪĖąŽč§.

C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąÍ≥ľ PRISA ž†źžąė I ŽįŹ II ÍįĀÍįĀžĚė žěÖžõź žėąžł° ŽŹĄÍĶ¨Ž°úžĄú žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ Ž∂ĄžĄĚŪēėÍ≥†, PRISA ž†źžąė I ŽįŹ IIžóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēžĚė žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀÍ≥ľ ŽĻĄÍĶźŪĖąŽč§. ÍĶ¨ž≤īž†ĀžúľŽ°ú, žěÖžõź žėąžł°žĄĪž†Ā Í≤Äž¶ĚžĚĄ žúĄŪēī ŽįĪŪėąÍĶ¨, C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßą, PRISA ž†źžąė I ŽįŹ II, SIRS ž†źžąė ÍįĀÍįĀžóź ŽĆÄŪēī receiver operating characteristic (ROC) Í≥°žĄ†žĚĄ Í∑łŽ¶į ŪõĄ AUCŽ•ľ Í≥ĄžāįŪēėžó¨ ŽĻĄÍĶźŪĖąŽč§. ÍįĀ ŽŹĄÍĶ¨žĚė ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ ŽįŹ ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄŽäĒ Youden indexÍįÄ žĶúÍ≥†žĚł ÍįížĚĄ žó≠žĻėŽ°ú Ūēėžó¨ ÍĶ¨ŪĖąŽč§. ŪÜĶÍ≥Ąž†Ā Ž∂ĄžĄĚžóźŽäĒ STATA ver. 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) ŽįŹ MedCalc ver. 18.9 (MedCalc Software BVBA, Ostend, Belgium)Ž•ľ žĚīžö©ŪĖąžúľŽ©į, P < 0.05Ž•ľ ŪÜĶÍ≥Ąž†Ā žú†žĚėžĄĪžĚī žěąŽäĒ Í≤ÉžúľŽ°ú ž†ēžĚėŪĖąŽč§.

Í≤įÍ≥ľ1. žĚľŽįėž†Ā ŪäĻžĄĪžóįÍĶ¨ÍłįÍįĄžóź Ž≥łžõź žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ Žį©Ž¨łŪēú 4ÍįúžõĒ-17žĄł Ūôėžěź 3,287Ž™Ö ž§Ď žóī ŪôėžěźŽäĒ 1,532Ž™ÖžĚīžóąŽč§. žó¨ÍłįžĄú Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨Ž•ľ žčúŪĖČŪēėžßÄ žēäžĚÄ 500Ž™ÖžĚĄ ž†úžôłŪēú žīĚ 1,032Ž™ÖžĚĄ Ž∂ĄžĄĚŪĖąŽč§. ž†úžôłŪēú 500Ž™ÖžĚė ŽāėžĚīžĚė ž§ĎžēôÍįížĚÄ 25ÍįúžõĒ(žā¨Ž∂ĄžúĄžąė Ž≤ĒžúĄ, 17-46.5ÍįúžõĒ)žĚīžóąÍ≥†, Žā®žěźÍįÄ 301Ž™Ö(60.2%)žĚīžóąžúľŽ©į ž≤īžė®žĚė ž§ĎžēôÍįížĚÄ 38.1‚ĄÉ (žā¨Ž∂ĄžúĄžąė Ž≤ĒžúĄ, 37.8‚ĄÉ-38.6‚ĄÉ)žėÄŽč§(Appendix 3).

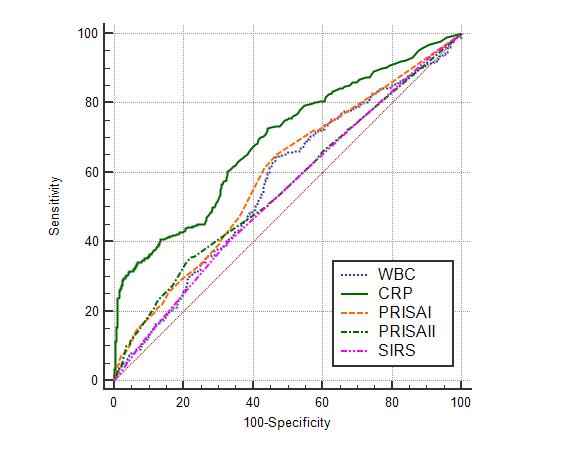

2. žěÖžõź žėąžł° ŽŹĄÍĶ¨ žĄĪž†Ā ŽĻĄÍĶźC-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßą, PRISA ž†źžąė I ŽįŹ II, SIRS ž†źžąėŽäĒ žěÖžõźÍĶįžóźžĄú žú†žĚėŪēėÍ≤Ć ŽÜížēėŽč§. ÍįĀ Žč®žĚľ ŽŹĄÍĶ¨žĚė AUCŽ•ľ ŽĻĄÍĶźŪēú Í≤įÍ≥ľ, C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė AUCÍįÄ 0.69 (95% žč†ŽĘįÍĶ¨ÍįĄ, 0.66-0.72)Ž°ú ÍįÄžě• žĽłÍ≥†, žĚīŽäĒ PRISA ž†źžąė I (AUC 0.59; 95% žč†ŽĘįÍĶ¨ÍįĄ: 0.56-0.62) ŽįŹ II (AUC 0.56; 95% žč†ŽĘįÍĶ¨ÍįĄ: 0.53-0.59)Ž≥īŽč§ žöįžąėŪĖąŽč§(Table 3, Fig. 1).

Youden indexŽ•ľ Í∑ľÍĪįŽ°ú žāįž∂úŪēú C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė ž†ąŽč®ÍįížĚÄ 34.3 mg/LžėÄÍ≥†, žĚī ÍįížóźžĄú ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ 28.8%, ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄ 97.5%žėÄŽč§. PRISA ž†źžąė IžĚÄ ž†ąŽč®Íįí 15ž†źžóźžĄú ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ 29.1%, ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄ 80.4%žėÄÍ≥†, PRISA ž†źžąė IIŽäĒ ž†ąŽč®Íįí 12ž†źžóźžĄú ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ 35.5%, ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄ 78.0%žėÄŽč§(Table 4).

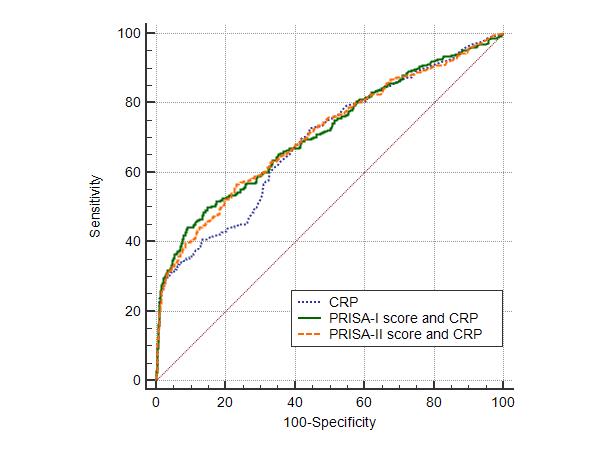

PRISA ž†źžąė Ižóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēžĚė AUCŽäĒ 0.71 (95% žč†ŽĘįÍĶ¨ÍįĄ: 0.69-0.74)žĚīžóąÍ≥†, PRISA ž†źžąė IIžóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēžĚė AUCŽäĒ 0.71 (95% žč†ŽĘįÍĶ¨ÍįĄ: 0.68-0.74)žėÄŽč§. PRISA ž†źžąė IÍ≥ľ IIžóź ÍįĀÍįĀ C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēÍ≥ľ C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßą Žč®ŽŹÖžĚľ ŽēĆ AUC ŪĀ¨ÍłįŽ•ľ ŽĻĄÍĶźŪēī Ž≥īŽ©ī, PRISA ž†źžąė Ižóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēŽßĆžĚī Ž≥īŽč§ ŪÜĶÍ≥Ąž†ĀžúľŽ°ú žú†žĚėŪēėÍ≤Ć AUCŽ•ľ ž¶ĚÍįÄžčúžľįŽč§(P = 0.048, P = 0.054) (Table 5, Fig. 2).

Í≥†žįįŽ≥ł žóįÍĶ¨ŽäĒ žÜĆžēĄ žóī ŪôėžěźžóźžĄú žěÖžõź žėąžł° ŽŹĄÍĶ¨žĚė žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ ŪŹČÍįÄŪēėžó¨, žÜĆžēĄžßĄŽ£Ć Í≤ĹŪóėžĚī Ž∂Äž°ĪŪēú žĚėžā¨žĚė žěÖžõź Í≤įž†ēžĚĄ ŽŹēŽäĒ Í≤ɞ̥ Ž™©ŪĎúŽ°ú žąėŪĖČŪĖąŽč§. PRISA I, II ž†źžąėžóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēžĚė AUC (0.71)ÍįÄ Žč®žĚľ ŽŹĄÍĶ¨ ž§Ď ÍįÄžě• žöįžąėŪēú C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė AUC (0.69)Ž≥īŽč§ ŽÜížēėžúľŽāė, PRISA II ž†źžąėžóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©Ūēú Ž™®ŪėēžĚÄ ŪÜĶÍ≥Ąž†ĀžúľŽ°ú žú†žĚėŪēėÍ≤Ć AUCŽ•ľ ž¶ĚÍįÄžčúŪā§žßÄŽäĒ žēäžēėŽč§. žĚīŽäĒ PRISA I ž†źžąėžóź C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ Í≤įŪē©ŪēėŽäĒ Í≤ÉžĚī žěÖžõź Í≤įž†ēžóź žú†žö©Ūē®žĚĄ žčúžā¨ŪēúŽč§.

C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚĄ žĚīžö©Ūēėžó¨ SBIŽ•ľ žėąžł°ŪēėŽäĒ žóįÍĶ¨žĚė Í≤įÍ≥ľŽ•ľ AUCŽ•ľ ž§Ďžč¨žúľŽ°ú žöĒžēĹŪēėŽ©ī Žč§žĚĆÍ≥ľ ÍįôŽč§. Pulliam ŽďĪ[7]žĚÄ 36ÍįúžõĒ žĚīŪēėžĚė žóī ŪôėžěźžóźžĄú C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė SBI žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ 70 mg/LŽ•ľ ž†ąŽč®ÍįížúľŽ°ú Ūē† ŽēĆ ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ 79%, ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄ 91%, AUC 0.91Ž°ú Ž≥īÍ≥†ŪĖąŽč§. IsaacmanÍ≥ľ Burke[8]ÍįÄ žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ Žį©Ž¨łŪēú 3-36ÍįúžõĒ žóī ŪôėžěźžóźžĄú C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė žě†žě¨ žĄłÍ∑†Ūėąž¶Ě(occult bacteremia) žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ 44 mg/LŽ•ľ ž†ąŽč®ÍįížúľŽ°ú Ūē† ŽēĆ ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ 63%, ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄ 81%, AUC 0.71Ž°ú Ž≥īÍ≥†ŪĖąŽč§. Hu ŽďĪ[9]žĚī C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßąžĚė SBI žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ Ž∂ĄžĄĚŪēú ž≤īÍ≥Ąž†Ā Ž¨łŪóĆÍ≥†žįįžóź ŽĒįŽ•īŽ©ī, ž†ąŽč®Íįí 8-20 mg/LžóźžĄú ŽĮľÍįźŽŹĄ 69%, ŪäĻžĚīŽŹĄ 75%žėÄÍ≥†, AUC 0.78žĚīžóąŽč§.

Miles ŽďĪ[13]žĚÄ žėĀÍĶ≠žóźžĄú PRISA I ž†źžąėžĚė AUCŽ•ľ 0.76žúľŽ°ú Ž≥īÍ≥†ŪĖąŽč§. Gravel ŽďĪ[14]žĚÄ žļźŽāėŽč§žóźžĄú žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ Žį©Ž¨łŪēú žÜĆžēĄŪôėžěźžóźžĄú žěÖžõź žėąžł°žĄĪž†ĀžĚĄ PRISA I ž†źžąėŽ•ľ ŪÜĶŪēėžó¨ ž†ĄŪĖ•ž†ĀžúľŽ°ú Ž∂ĄžĄĚŪēú Í≤įÍ≥ľ, AUC 0.79Ž°ú Ž≥īÍ≥†ŪĖąŽč§.

Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨žóźžĄú PRISA I ž†źžąėžôÄ PRISA II ž†źžąėžĚė AUCŽäĒ žĚīž†Ą ŪÉÄŽčĻŽŹĄ Í≤Äž¶ĚžóźžĄú Ž≥īÍ≥†Žźú AUCŽ≥īŽč§ ŽĻĄÍĶźž†Ā ŽāģžĚÄ Í≤ÉžĚÄ Žč§žĚĆÍ≥ľ ÍįôžĚÄ žõźžĚłžóź ÍłįžĚłŪēú Í≤ÉžúľŽ°ú ž∂Ēž†ēŪēúŽč§. ž≤ęžßł, Ž≥ł ŪõĄŪĖ•ž†Ā žóįÍĶ¨žóźžĄú Ž≥ĎŽ†•ž≤≠ž∑® žčú PRISA ž†źžąėžóź ŪēĄžöĒŪēú Ūē≠Ž™©žĚī ŽąĄŽĚĹŽźėžĖī ž†źžąėÍįÄ žÉĀŽĆÄž†ĀžúľŽ°ú ŽāģÍ≤Ć žł°ž†ēŽźźžĚĄ žąė žěąŽč§. ŽĎėžßł, žĚĎÍłČžč§ Ūáīžõź žĚīŪõĄ 49Ž™Ö(8%)žĚė ŪôėžěźÍįÄ žôłŽěė ŽįŹ žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ ŪÜĶŪēėžó¨ žě¨Žį©Ž¨łŪĖąžúľŽ©į žĚī ž§Ď 39Ž™Ö(71%)žĚī žěÖžõźŪĖąŽč§. žĚīŽäĒ ŪõĄŪĖ•ž†Ā ŽćįžĚīŪĄįŽ°ú žąėžßĎžúľŽ°ú PRISA ž†źžąėžĚė ž†ēŪôēŽŹĄÍįÄ žėĀŪĖ•žĚĄ ŽįõžēėžĚƞ̥ žčúžā¨ŪēúŽč§. žÖčžßł, Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨žóźžĄú žěÖžõź Í≤įž†ēžóź žĚėŪēôž†Ā žÉĀŪÉú žôłžóź Ž≥īŪėłžěźžĚė žöĒÍĶ¨ÍįÄ ŽćĒ ŪĀį žėĀŪĖ•žĚĄ ŽĮłžĻú ŪôėžěźÍįÄ žĚľŽ∂Ä ŪŹ¨Ūē®ŽźźŽč§ŽäĒ ž†źžĚīŽč§.

Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨žĚė ž†úŪēúž†źžĚÄ Žč§žĚĆÍ≥ľ ÍįôŽč§. ž≤ęžßł, žīĚ 1,532Ž™ÖžĚė žóī Ūôėžěź ž§Ď 500Ž™ÖžĚī Ūėąžē°Í≤Äžā¨ ŽąĄŽĚĹžúľŽ°ú ž†úžôłŽźėžĖī ŽĻĄŽö§Ž¶ľžĚė ÍįÄŽä•žĄĪžĚī žěąŽč§. ŽĎėžßł, Žč®žĚľÍłįÍīĞ󟞥ú žčúŪĖČŪēú ŪõĄŪĖ•ž†Ā Ž∂ĄžĄĚžúľŽ°ú žĚľŽįėŪôĒÍįÄ žĖīŽ†§žöł žąė žěąŽč§.

Í≤įŽ°†ž†ĀžúľŽ°ú, Ž≥ł žóįÍĶ¨žóźžĄú žĚĎͳȞ觞̥ Žį©Ž¨łŪēú žÜĆžēĄ žóī ŪôėžěźžóźžĄú PRISA I scorežôÄ C-ŽįėžĚώ讎įĪžßą Í≤įŪē©Ž™®ŪėēžĚĄ ŪÜĶŪēī žěÖžõźžĚĄ Ūö®Í≥ľž†ĀžúľŽ°ú žėąžł°Ūē† žąė žěąžóąŽč§. ŪĖ•ŪõĄ ž†ĄŪĖ•ž†ĀžĚł žóįÍĶ¨ÍįÄ ŪēĄžöĒŪēėŽč§Í≥† žÉĚÍįĀŪēúŽč§.

Fig. 1.Comparison of area under the curves (AUCs) for hospitalization among the individual admission decision support tools using receiver operating characteristic curves. AUC for white blood cell (WBC), 0.57 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.60); for C-reactive protein (CRP), 0.69 (95% CI, 0.66-0.72); for the Pediatric Risk of Admission (PRISA) score I, 0.59 (95% CI, 0.56-0.62); for the PRISA score II: 0.56 (95% CI, 0.53-0.59); and for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) score, 0.54 (95% CI, 0.51-0.58).

Fig. 2.Comparison of area under the curves (AUCs) for hospitalization of isolated C-reactive protein (CRP) and the 2 combined models of the PRISA scores and CRP using receiver operating characteristic curves. AUC for CRP, 0.69 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66-0.72); for Pediatric Risk of Admission (PRISA) score I and CRP, 0.71 (95% CI, 0.69-0.74); and for PRISA score II and CRP, 0.71 (95% CI, 0.68-0.74). AUC of combined model of the PRISA score I and CRP vs that of the isolated CRP (P = 0.048) and AUC of combined model of the PRISA score II and CRP versus that of the isolated CRP (P = 0.054).

Table 1.Clinical characteristics of the study population (N = 1,032) Table 2.Causes of fever Table 3.Comparison of admission decision support tools between the hospitalization and discharge groups Table 4.Comparison of AUCs for hospitalization among the individual admission decision support tools

References1. Kim DK, Kwak YH, Lee SJ, Jung JY, Song BK, Lee JH, et al. A national survey of current practice patterns and preparedness of pediatric emergency care in Korea. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2012;23:126‚Äď31. Korean.

2. Kwak YH. Current status and future direction of pediatric emergency medicine in Korea. Pediatr Emerg Med J 2014;1:1‚Äď10. Korean.

3. Kwak BG, Jang HO. Clinical analysis of febrile infants and children presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Korean J Pediatr 2006;49:839‚Äď44. Korean.

4. Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE, Pollack MM. Pediatric Risk of Admission (PRISA): a measure of severity of illness for assessing the risk of hospitalization from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:161‚Äď9.

5. Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Pollack MM. The Pediatric Risk of Hospital Admission Score: a second-generation severity-of-illness score for pediatric emergency patients. Pediatrics 2005;115:388‚Äď95.

6. Lacour AG, Gervaix A, Zamora SA, Vadas L, Lombard PR, Dayer JM, et al. Procalcitonin, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1 receptor antagonist and C-reactive protein as identificators of serious bacterial infections in children with fever without localising signs. Eur J Pediatr 2001;160:95‚Äď100.

7. Pulliam PN, Attia MW, Cronan KM. C-reactive protein in febrile children 1 to 36 months of age with clinically undetectable serious bacterial infection. Pediatrics 2001;108:1275‚Äď9.

8. Isaacman DJ, Burke BL. Utility of the serum C-reactive protein for detection of occult bacterial infection in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:905‚Äď9.

9. Hu L, Shi Q, Shi M, Liu R, Wang C. Diagnostic value of PCT and CRP for detecting serious bacterial infections in patients with fever of unknown origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2017;25:e61‚Äď9.

10. Honda T, Uehara T, Matsumoto G, Arai S, Sugano M. Neutrophil left shift and white blood cell count as markers of bacterial infection. Clin Chim Acta 2016;457:46‚Äď53.

11. El-Radhi AS, Patel S. An evaluation of tympanic thermometry in a paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J 2006;23:40‚Äď1.

12. Chamberlain JM, Terndrup TE, Alexander DT, Silverstone FA, Wolf-Klein G, O'Donnell R, et al. Determination of normal ear temperature with an infrared emission detection thermometer. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:15‚Äď20.

13. Miles H, Litton E, Curran A, Goldsworthy L, Sharples P, Henderson AJ. The PATRIARCH Study. Using outcome measures for league tables: can a North American prediction of admission score be used in a United Kingdom children's emergency department? PRISA And Triage In A Regional Children's Hospital. Emerg Med J 2002;19:536‚Äď8.

AppendicesAppendix 1.Component of the PRISA score IAppendix 2.Components of PRISA score II |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|