|

|

AbstractPurposeTo investigate the age group characteristics of children who visited the emergency department with acute poisoning by ingestion.

MethodsWe reviewed children under 19 years who visited the emergency department for acute poisoning by ingestion from 2012 to 2017. The children were divided into 3 age groups; infants (0-1 years), preschoolers (2-5 years), and schoolers (6-18 years). Clinical characteristics, intentional ingestion, involved substances (drugs, household products, artificial substances, and pesticides), decontamination and antidote therapy, and outcomes of the 3 age groups were compared. We also performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with hospitalization.

ResultsA total of 622 children with acute poisoning by ingestion were analyzed. Their annual proportions to overall pediatric emergency patients ranged from 0.3% to 0.4%. Age distribution showed bimodal peaks at 0-2 years and 15-17 years. The infants showed lower frequency of girls, intentional ingestion, ingestion of drugs, performance of decontamination and antidote therapy, and hospitalization than 2 older groups (P < 0.001). Most decontamination, antidote therapy, and hospitalization occurred in the schoolers (P < 0.001). The most frequently reported substances were household cleaning substances in the infants (18.2%), antihistamines in the preschoolers (15.8%), and analgesics in the schoolers (37.5%). The factors associated with hospitalization were intentional ingestion (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 7.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.85-17.61; P = 0.001) and schoolers (aOR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.10-7.53; P = 0.031; compared with infants). Only 1 in-hospital mortality was found in a boy aged 2 years who ingested methomyl.

ConclusionInfants may experience non-intentional ingestion, ingestion of non-pharmacologic substances (especially household cleaning substances), discharge without decontamination and antidote therapy more frequently than older children. Thus, we need age group-specific, preventive and therapeutic plans for children with acute poisoning.

서론중독 환자는 응급실 입원환자의 0.7%-5.5%를 차지하며[1,2], 소아에서 질병 외 응급환자의 2%-5%를 차지한다[3-6]. 소아 중독의 특성은 2세 이하의 영유아, 저독성, 저용량, 단일 독성물질, 비의도적 중독이 비교적 흔하다는 점이다[7-9]. 1997년 국내보고에 따르면 소아 중독의 사망률은 1.1%로 보고됐다[6]. 이처럼 중독은 치사율은 낮으나 치명적인 중독의 경우 심각한 후유증을 남기거나 사망에 이르게 할 수 있다[7]. 또한, 최근에는 일반의약품이 증가하고 편의점에서도 의약품을 판매하는 등 약물에 대한 접근성이 좋아지고 독성물질을 시중에서 쉽게 구하는 경우가 많아 소아가 독성물질에 노출되는 상황이 증가했다[7,10,11].

대상과 방법본 연구는 2012년 1월 1일부터 2017년 12월 31일까지 인천의 단일기관 응급실을 방문한 18세 이하 섭취를 통한 급성중독 환자의 의무기록을 분석했다. 인천의 인구는 약 3,010,000명으로, 농어촌 및 산업 지역을 포함하는 도농복합 지역이다[14]. 본원은 연간 약 100,000명의 응급환자(소아 약 31,000명 포함)가 방문하는 인천 권역응급의료센터이다.

급성중독은 응급실 방문 전 24시간 이내에 독성물질을 섭취한 경우로 정의했다. 단, 음주, 절지동물 교상, 흡입(일산화탄소, 휘발물질 등) 또는 피부 노출은 제외했다. 연구대상자의 임상적 특성으로 방문 시기(년, 계절, 월), 나이(년), 성별, 의도적 중독 여부, 독성물질 종류, 오염제거(위세척, 활성탄 투여)와 해독제 요법, 응급실 치료 결과(일반병실 및 중환자실 입원, 자의퇴원, 입원기간, 원내사망)를 조사했다. 의도적 중독만, 정신질환과 자살시도의 비율을 조사했다. 연구대상자의 나이대는 영아기(0-1세), 학령전기(2-5세), 학령기(6-18세)로 분류했다. 계절은 방문일을 기준으로 봄(3-5월), 여름(6-8월), 가을(9-11월), 겨울(12-2월)로 구분했다. 독성물질 종류는 2016년 American Association of Poison Control Centers 보고[15]에 준하여 20종으로 분류하고, 이를 소분류로 정의했다(Appendix 1). 본 저자는 이를 다시 4종으로 분류하고, 이를 대분류로 정의했다(Appendix 2).

통계적 분석은 SPSS ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY)을 사용했다. 나이대별 특성을 분석하기 위해, 범주형 자료는 chi-square test를, 연속형 자료는 ANOVA test를 각각 사용했다. 입원 예측인자를 분석하기 위해 단변수 분석에서 P < 0.05인 변수를 포함하여 다변수 로지스틱 회귀분석을 시행했다. 통계적 유의성은 P < 0.05으로 정의했다. 본 연구는 본원 임상연구심의위원회의 승인을 받고 시행했다(IRB No: GCIRB2018-111).

결과1. 일반적 특성연구기간에 본원 응급실을 방문한 급성중독 환자 총 798명 중, 흡입중독 121명(일산화탄소 96명), 음주 43명, 절지동물 교상 12명을 제외한 622명을 분석했다. 제외된 176명의 환자 중 영아기는 15명(8.5%), 학령전기 56명(31.8%), 학령기 105명(59.7%)이었고, 학령기 환자 중 청소년(13-18세)은 84명(47.7%) 이었다. 연구대상자 나이의 중앙값은 2세(사분위수 범위, 1-13세)였고, 이 중 여자가 328명(52.7%)이었다.

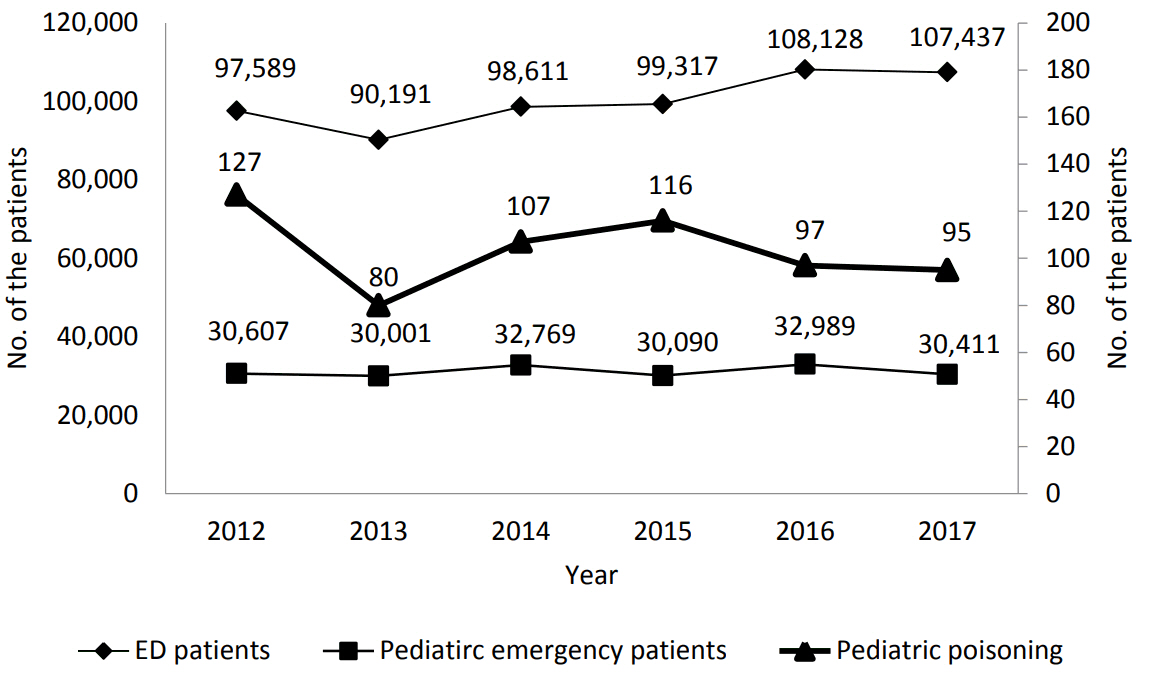

급성중독 환자의 연도별 분포는 소아응급환자의 0.3%-0.4%로 비교적 일정했다(Fig. 1). 계절별 분포는 봄에 182명(29.3%)으로 가장 많은 환자가 방문했고, 가을 161명(25.9%), 여름 146명(23.5%), 겨울 133명(21.4%) 순이었다. 월별로는 5월에 71명(11.4%)으로 가장 많았고, 9월 60명(9.6%), 4월 59명(9.5%)이 그 뒤를 이었다.

나이별 분포에서 전반적으로 0-2세와 15-17세에 이정점 분포(bimodal distribution)를 보였고, 1세가 212명(34.1%)으로 가장 많았다(Fig. 2). 나이대별 분포에서 영아기 292명(46.9%), 학령전기 146명(23.5%), 학령기 184명(29.6%)으로, 영아기에 가장 많은 환자가 발생했다. 학령기 중 13-18세는 163명(26.2%)이었다. 학령기에 여자 비율이 가장 높았다(71.2%). 의도적 중독 148명(23.8%)은 모두 학령기에 발생했다(P < 0.001) (Table 1). 이 중 정신질환 과거력 및 자살의도가 확인된 환자는 각각 45명(30.4%)과 51명(34.5%)이었다. 의도적 중독 환자 중 최연소자는 12세였다.

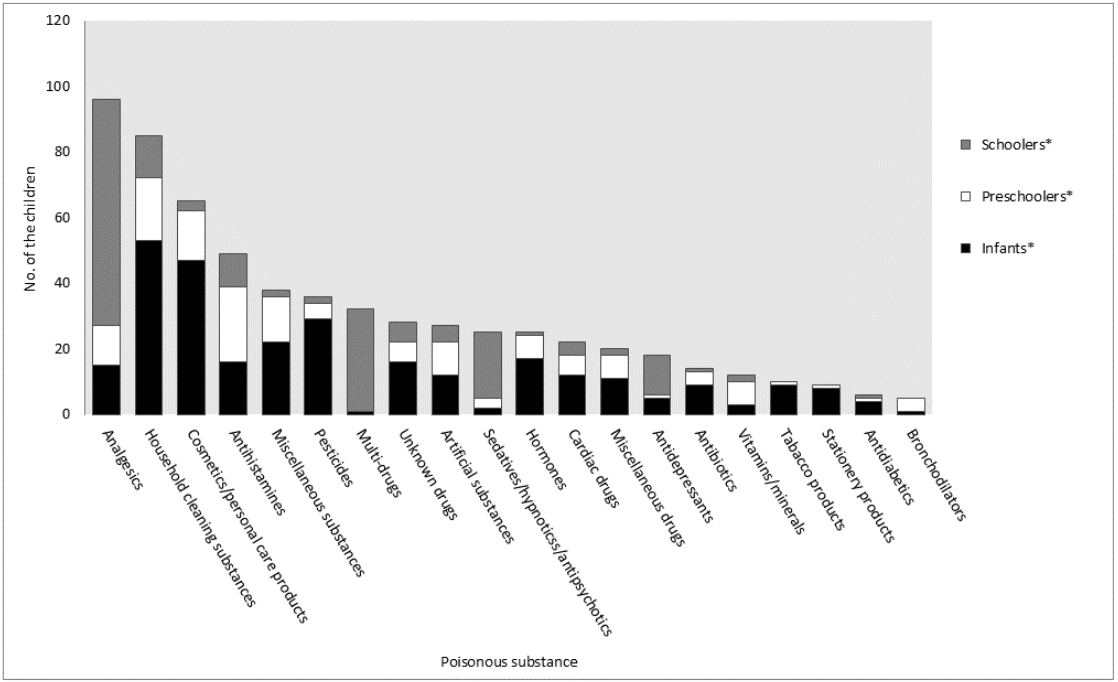

2. 임상적 특성 및 치료 결과독성물질의 대분류(Appendix 2)에서 약물이 351명(56.4%)으로 가장 많았고, 가정 내 생활용품(174명, 28.0%), 인공 독성물질(61명, 9.8%), 농약(36명, 5.8%) 순이었다(Table 1). 영아기에는 가정 내 생활용품(119명, 40.8%), 학령기에는 약물(159명, 86.4%)이 각각 가장 흔했다(P < 0.001). 소분류(Appendix 1)에서 진통제가 96명(15.4%)으로 가장 흔했고(Appendix 3), 가정용 세척제(85명, 13.7%) (Appendix 4), 개인용품/화장품(65명, 10.5%), 항히스타민제(49명, 7.9%), 기타 비약물 독성물질(38명, 6.1%) 순이었다(Fig. 3). 나이대별로 가장 흔한 독성물질은 영아기, 학령전기, 학령기에 각각 가정용 세척제(53명, 18.2%), 항히스타민제(23명, 15.8%), 진통제(69명, 37.5%)였다(Table 2).

오염제거 또는 해독제 요법을 경험한 환자 115명(18.5%) 중 112명이 학령기 환자로, 다른 나이대에 비교해 그 빈도가 높았다(P < 0.001) (Table 1). 특히 해독제 투여받은 환자 43명 중 41명이 학령기 환자였다. 이 중 40명에게 acetaminophen 중독으로 N-acetylcysteine을, 1명에게 organophosphate 중독으로 atropine과 pralidoxime을 각각 투여했다. 영아기 또는 학령전기에서 오염제거를 경험한 환자는 응급실 방문 1시간 전 nitroglycerin 12 mg을 섭취한 2세 남자 1명이었다. 해독제 요법을 경험한 환자는 2명으로, 이 중 1세 여자(acetaminophen 2,600 mg)에게 N-acetylcysteine을, 2세 남자(methomyl [carbamate], 섭취량 미상)에게는 atropine을 각각 투여했다. 이 2세 남자 환자는 유일한 원내사망 환자로, 중환자실 입원했으나 다발장기부전으로 제2병일에 사망했다

학령기 환자 중 89명(48.4%)이 일반병실로, 19명(10.3%)이 중환자실로 각각 입원했고, 다른 나이대 보다 입원 빈도가 높았다(P < 0.001). 전체 입원환자 151명의 입원기간 중앙값은 3.0일(사분위수 범위, 2.0-4.0일)이었다. 중환자실 입원 환자 20명의 독성물질 종류는 2가지 이상의 약물이 8명으로 가장 많았다(Table 3).

고찰본 연구는 본원 응급실을 방문한 섭취를 통한 급성중독 환자는 나이대별로 다른 특성을 보이며, 이 중 영아의 여성, 의도적 중독, 약물 중독, 오염제거와 해독제 요법 시행, 입원 빈도가 낮았음을 보여준다. 오염제거와 해독제 요법, 입원은 주로 학령기에 이뤄졌고, 입원 예측인자는 의도적 중독과 학령기 나이대였다. 나이대별로 가장 흔한 독성물질은 가정용 세척제(영아기), 항히스타민제(학령전기), 진통제(학령기)였다.

연구기간 동안 연간 환자 수(약 30,000명)와 전체 응급환자 대비 비율(0.3%-0.4%)은 대체로 일정했다. 이 비율은 전체 중독 환자(성인 포함)의 빈도인 0.4%와 비슷한 결과였다[16]. 계절별로 봄(특히 5월)에 환자가 가장 많았던 것은, 1985-1996년에 단일기관 급성중독 입원 빈도가 5월에 가장 높았던 것과 일치한다[17]. 나이별로 0-2세 비율이 가장 높고 15-17세에 두 번째로 높은 비율을 보이는 이정점 분포는 이전 연구와 일치했다[6,8,13]. 중독 환자 중 청소년 비율은 2008년 이전에 12.0%-25.5%로 보고됐지만[18,19], 2008-2012년에는 38.0%로 증가하는 경향을 보였다[8]. 본 연구기간이 2012년 이후임을 고려하면, 청소년 비율(26.2%)이 낮은 경향을 보였다. 하지만, 본 연구에서 청소년 84명을 제외한 것을 고려하면, 전체 중독(섭취와 무관) 환자 중 청소년 비율은 전술한 38.0%에 근접했을 것으로 추정한다.

학령기에서 여자 비율(71.2%)은 이전 보고와 유사했다[3,8]. 의도적 중독은 학령기 환자 중 80.4%를 차지했고 다른 나이대에서는 발견하지 못했으며, 이 점은 이전 보고와 유사했다[8,9,16]. 독성물질에서 약물이 가장 흔했던 것(56.4%)은 이전 연구3,8)와 유사했지만, 가정 내 생활용품 빈도(28.0%)는 높고 농약 빈도(5.8%)는 낮은 경향을 보였다[3,8,18]. 6세 미만(영아기 및 학령전기)에서 비약물 중독(246명, 56.2%), 가정용 세척제(72명, 16.4%), 화장품/개인용품(62명, 14.2%)의 빈도가 높았던 것은 2016년 American Association of Poison Control Centers 보고[15]에서 가정용 세척제와 화장품/개인용품 빈도를 각각 11.1%와 13.3%로 보고한 것과 유사했다. 약물 중 진통제(학령기)와 항히스타민제(학령전기)가 흔한 것은 자주 처방되는 일반의약품이라는 점에 기인한 것으로 추정한다. 오염제거와 해독제 요법, 입원을 경험한 환자는 대개 학령기였고, 이는 입원 예측인자가 의도적 중독과 학령기인 것과 일맥상통한다. 학령기에 의도적 중독 빈도가 높고, 의도적 복용은 과량 복용과 연관된다[20]. 학령기에 해독제 투여 빈도(22.3%)는 11-18세 환자 중 29.7%가 해독제 요법을 경험했다는 보고보다 낮은 경향을 보였다[8]. 이는 일산화탄소 중독을 제외한 것에 기인한 것으로 해석할 수 있다.

영아기 및 학령전기에는 오염제거, 해독제 요법, 입원 필요성이 떨어지는 비의도적 중독이 흔하므로, 보호자의 주의 또는 시간외 의료서비스를 통해 대부분 예방할 수 있다. 구체적으로, 보호자는 독성물질을 어린이가 접근하기 어려운 곳에 보관하고, 약물 용량 및 용법을 숙지하여 오남용을 줄여야 한다. 학령기는 전술한 영아기 및 학령전기 중독 환자와 반대의 특성을 가지므로, 가정, 학교, 국가의 다각적 측면에서 접근해야 한다. 특히, 이 나이대의 높은 정신질환 유병률로 인해 잠재적으로 치명적인 항우울제, 항정신병약의 처방이 늘고 있어, 주의를 요한다[9,21]

본 연구의 제한점은 다음과 같다. 첫째, 단일기관에 기반한 결과이므로 일반화에 어려움이 있을 수 있다. 둘째, 의무기록에 방문 당시 상황이 불충분하게 기술된 점이 결과에 영향을 미쳤을 수 있다. 이 때문에 독성물질을 미상으로 분류하거나, 섭취량, 섭취시각, 동반 증상을 분석하지 못했다. 셋째, 사춘기 환자의 특성을 별도로 분석하지 못했다. 이는 학령기 환자 중 6-12세 환자가 21명에 불과하여, 별도의 나이대로 분류하면 chi-square test로 분석하기 어려웠기 때문이다.

본 연구는 섭취를 통한 급성중독은 나이대별로 다른 특성을 보이며, 구체적으로 영아기에 비의도적, 비약물 중독이 흔하고, 오염제거와 해독제 요법 및 입원은 주로 학령기에 해당한다는 점을 시사한다. 중독 환자의 나이대에 따른 특성을 활용하여, 응급의료자원을 효율적으로 활용하는 치료 계획과 가정, 학교, 국가 차원의 예방 대책을 세울 수 있기를 기대한다.

Fig. 1.Annual trend of the children who visited the emergency department with acute poisoning by ingestion from 2012 to 2017. Their annual proportions to overall pediatric emergency patients show relatively consistent trend, ranging from 0.3% (80 of the 30,001 children, in 2013) to 0.4% (127 of the 30,607 children, in 2012). ED: emergency department.

Fig. 3.Frequently reported substances. The most frequently reported substances were household cleaning substances in the infants (8.5%), antihistamines in the preschoolers (3.7%), and analgesics in the schoolers (11.1%). *Infants, preschoolers, and schoolers refer to children aged 0-1 years, 2-5 years, and 6-18 years, respectively.

Table 1.Age group characteristics of the children who visited the emergency department with acute poisoning by ingestion (N = 662)

* Infants, preschoolers, and schoolers refer to children aged 0-1 years, 2-5 years, and 6-18 years, respectively. Table 2.Age group characteristics of frequently reported substances (N = 662)

Table 3.The children hospitalized to the intensive care unit (N = 20)

References1. Jang HS, Kim JY, Choi SH, Yoon YH, Moon SW, Hong YS, et al. Comparative analysis of acute toxic poisoning in 2003 and 2011: analysis of 3 academic hospitals. J Korean Med Sci 2013;28:1424–30.

2. Song KJ, Cho KH, Lee HS. Drug intoxication patients in the emergency department. J Korean Soc Emerg Med 1992;3:38–45. Korean.

3. Gauvin F, Bailey B, Bratton SL. Hospitalizations for pediatric intoxication in Washington State, 1987-1997. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:1105–10.

4. Lamireau T, Llanas B, Kennedy A, Fayon M, Penouil F, Favarell-Garrigues JC, et al. Epidemiology of poisoning in children: a 7-year survey in a paediatric emergency care unit. Eur J Emerg Med 2002;9:9–14.

6. Lee MJ, Park JS. Clinical aspects of injury and acute poisoning in Korean pediatric patients. Korean J Pediatr 2008;51:116–21. Korean.

7. Winston AB, Das Adhikari D, Das S, Vazhudhi K, Kumar A, Shanthi Fx M, et al. Drug poisoning in the community among children: a nine years' experience from a tertiary care center in south India. Hosp Pract (1995) 2017;45:21–7.

8. Han CS, Jeon WC, Min YG, Choi SC, Lee JS. Retrospective analysis on the clinical differences of children and adolescents treated for acute pediatric poisoning in an emergency department? J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2013;24:742–9. Korean.

9. Kim YJ, So BH, Kim HM, Jeong WJ, Cha KM, Kim SW. Analysis of clinical characteristics by gender in children and adolescents with intentional poisoning at emergency department. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol 2014;12:63–9. Korean.

10. Kim JS, Lee OS, Lim SC. Evaluation of drug information for acquisition methods and risk of drug misuse in Korean students. Yakhak Hoeji 2013;57:55–62. Korean.

11. Lee SY. A study of factors influencing drug use in high school students. J Korean Acad Nurs 1997;27:777–86. Korean.

12. Lam LT. Childhood and adolescence poisoning in NSW, Australia: an analysis of age, sex, geographic, and poison types. Inj Prev 2003;9:338–42.

13. Andiran N, Sarikayalar F. Pattern of acute poisonings in childhood in Ankara: what has changed in twenty years? Turk J Pediatr 2004;46:147–52.

14. Incheon Metropolitan City. Population of Incheon [Internet]. Incheon (Korea): Incheon Metropolitan City: c2018[cited 2018 May 11]. Available from: http://www.incheon.go.kr/articles/10417.

15. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, Fraser MO, Banner W. 2016 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2017;55:1072–252.

16. Lee JH, Oh SH, Park KN, Youn CS, Kim SH, Jeong WJ, et al. Epidemiologic study of poisoned patients who presented to the emergency department of a high end medical facility in Seoul 1998-2009. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol 2010;8:7–15. Korean.

17. Kong HP, Park KB, Lee OK, Park KS. The statistical study of patient with acute poisoning. Korean J Pediatr 1997;40:1596–602. Korean.

18. Kim DK, Choi KC, Jung EK, Yang ES, Moon KR. The clinical study of acute poisoning in children. Korean J Pediatr 1996;39:1753–8. Korean.

19. Mintegi S, Fernandez A, Alustiza J, Canduela V, Mongil I, Caubet I, et al. Emergency visits for childhood poisoning: a 2-year prospective multicenter survey in Spain. Pediatr Emerg Care 2006;22:334–8.

AppendicesAppendix 1.Minor categories of substances [15]Appendix 2.Major categories of substances |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|