Introduction

Spinal epidural hematoma (EDH) can occur after substantial spinal trauma, originating from thin-walled venous plexus lying to the spinal cord. Clinically significant traumatic spinal EDH occurs uncommonly [1]. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a post-infectious autoimmune demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy mainly involving motor and/or sensory and autonomic nerves. Clinical manifestations of these 2 entities are similar though they belong to different categories. Thus, both diagnoses should be initially considered in children presenting with leg weakness. In this report we describe a boy with traumatic spinal EDH masquerading as GBS, who recovered without neurologic sequelae owing to a rapid diagnosis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 2019-09-032).

Case

A 14-year-old boy was referred to the emergency department for sudden onset of tingling sensation on both hands and feet. He also complained of motor weakness in both legs and inability to walk. The boy was previously healthy, and denied having any recent respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms.

When he arrived at the emergency department, the initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 126/76 mmHg; heart rate, 67 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and temperature, 36.2°C. Neurological examination showed muscle strength of 3/5 on both legs. His sensory perception and both knee jerks were intact, and Babinski sign was negative bilaterally. Laboratory findings, including complete blood count, chemistry, electrolytes, and coagulation, were within normal limits. Initially, brain MRI showed no abnormal findings, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study showed normal concentration of protein (51.6 mg/dL), glucose (65 mg/dL), and white blood cell count (< 5 /mm3). Based on his ascending paralysis, we started intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for presumed GBS.

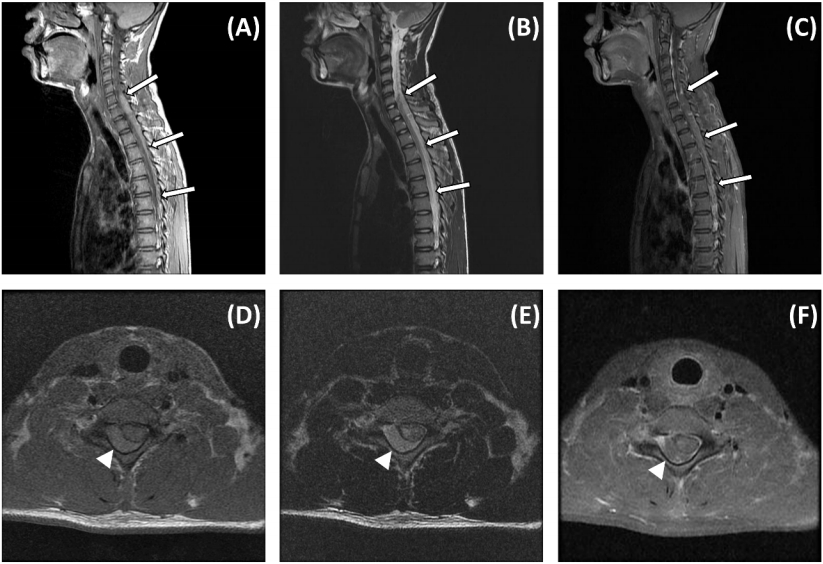

Despite the therapy, motor weakness progressed over 8 hours, resulting in complete loss of sensorimotor function below T4, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and positive Babinski sign. Due to the unusually rapid progression, whole spine MRI was performed to rule out spinal cord lesions. The MRI showed a large spinal EDH over the C5-T5 level with severe cord compression (Fig. 1). Emergency decompressive laminectomy and hematoma removal (C7-T3) were performed. During the operation, dark brown friable hematoma was noted, and fibroadipose tissue with hemorrhage and congestion without vascular abnormalities were shown in pathology.

Thorough review of the boyâs recent activities, particularly of trauma history, revealed a whiplash injury on an amusement ride that he had experienced about 3 weeks prior to the symptom onset. He also disclosed neck and shoulder pain that had worsened 2 days before. After early vigorous postoperative rehabilitation, on the fifth week of follow-up, his sensory-motor function was fully recovered.

Discussion

Incidence of acute spinal cord injury in children ranges from 5 to 40 cases per million [2]. Mechanism of injury can be classified as follows: forward ï¬exion, lateral ï¬exion, rotation, axial compression, and hyperextension. Among these, hyperextension, also known as whiplash injury, usually occurs during motor vehicle accidents or physically demanding exercise [3,4].

Spinal EDH is an extramedullary extradural injury of the spinal cord, that is, a hemorrhage in the space between the dura mater and overlying spine. Spinal trauma, the most common cause of spinal EDH, tears the thin-walled venous plexus located within the epidural space, resulting in the EDH. Depending on the rate and size of hematoma formation, spinal cord compression may manifest over hours to weeks [5]. In older children and adolescents, it is usually accompanied by severe neck or back pain aggravated by neck flexion or pressure over the spine. Spinal EDH is a potentially life-threatening entity warranting surgical intervention.

GBS in children usually presents as an afebrile, post-infectious illness characterized by acute or subacute progression of neurologic deficits, followed by variable courses of recovery. The children typically show symmetric ascending paralysis and diminished or absent deep tendon reflexes [6]. GBS can be mimicked by many diseases, including compression myelitis due to spinal EDH, transverse myelitis, hypokalemic periodic paralysis, myopathy, and myasthenia gravis [7]. In addition to the similarity in the manifestations of GBS and the mimickers, there are 2 factors preventing early diagnosis of GBS. First, it is often hard to find the key features, such as back pain and Babinski sign, in an uncooperative child. Second, albumin-cytologic dissociation, a typical cerebrospinal fluid profile, is present in less than half of children with the disease during the first week of illness. Thus, it is worth noting that the absence of albumin-cytologic dissociation alone does not rule out GBS [6].

Because spinal cord lesions are potentially life-threatening, misdiagnosis may cause critical results. Thus, rapidly progressive motor weakness in children with presumed GBS needs differential diagnosis using MRI in addition to thorough history taking and physical exam. This approach can aid in accurate diagnosis, treatment, and better prognosis. Although lumbar puncture would be a useful ancillary test, decompression of the subarachnoid space may exacerbate the spinal cord lesion, especially in children with hematoma in the space.

There have been 3 case reports of childrenâs spontaneous spinal EDH mimicking GBS [8-10]. All reported children presented with inability to walk, and underwent intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, but developed ascending paralysis. MRIs that were performed after a few days showed spinal EDHs needing emergency operation. The children showed complications with severe neurologic sequelae, except 1 child with a smaller lesion.

To the authorsâ best knowledge, this is the first case of traumatic spinal EDH masquerading as GBS with complete neurologic recovery. Close inspection and thorough review of the childrenâs history should be underscored when they present with ascending paralysis. Also, emergency MRI is required if neurologic deficits show rapid progression of the manifestations that is unusual for GBS.