소아응급전담전문의 진료 도입에 따른 소아응급진료 양상 변화

Changes in the characteristics of pediatric emergency practice following the introduction of pediatric specialist care

Article information

Trans Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to evaluate whether pediatric emergency practice has improved since the introduction of pediatric specialist care (PSC).

Methods

Retrospective observational study was conducted using the data retrieved from the emergency department (ED) of a tertiary university hospital in Cheongju, Korea. Patients younger than 19 years who visited the ED from January 2019 through December 2023 were enrolled in this study. Hospitalization (overall and intensive care unit [ICU]), in-hospital mortality, and return visit within 24 hours were compared between the periods before (January 2019- January 2021) and after (June 2021-December 2023) the introduction of PSC. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the outcomes using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

During the study period, a total of 36,162 patients visited the ED. The visits increased from 12,196 before to 22,387 after the introduction of PSC (increase by 83.6%). Annual numbers of the visits have increased since 2020 and reached 10,942 in 2023. After the introduction of PSC, decreases were noted in the hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.72) and return visit within 24 hours (0.73; 0.61-0.88). Hospitalization to the ICU increased (2.90; 2.29-3.69), while there was no significant difference in the in-hospital mortality (1.31; 0.77-2.25).

Conclusion

After the introduction of PSC, overall hospitalization and return visit decreased, while hospitalization to the ICU increased without a difference in the in-hospital mortality. Multidisciplinary efforts are needed to continue providing the pediatric specialist-centered emergency practice.

서론

저출산으로 인해 한국 소아 인구는 2011년 9,921,012명에서 2023년 7,077,206명으로 감소했지만, 소아환자의 응급실 방문은 2020년 이후 증가하여 2022년 현재 전체 응급실 방문의 17.0%를 차지한다(1,2). 이 추세에도 불구하고, 많은 응급실 의사는 여전히 소아진료에 부담을 느끼고 있으며, 소아응급진료를 위한 응급실 인력 및 지원은 불충분한 실정이다(3,4). 한국에서는 소아응급진료 수준을 높이기 위해 2010년부터 소아전용 응급실을 구축하여 운영했으며 2016년부터 중증 진료를 위해 소아전문응급의료센터(전문센터) 사업을 시작했다. 2023년 12월 현재 소아전용 응급실 3개소, 전문센터 10개소가 각각 운영 중이며, 2024년 1월 전문센터 2개소가 추가 선정됐다. 충청남도 천안의 3차 의료기관에서 소아전용 응급실 개설 이후 소아환자가 63% 증가했지만, 응급실 체류시간은 1.9시간에서 1.4시간으로 단축됐다(5). 또한, 소아응급전담전문의(전담전문의) 중심 진료는 환자 및 보호자의 만족도를 높일 수 있다(6,7). 본원은 2021년 5월부터 5명의 전담전문의 진료 체제를 운영했고, 이에 따라 소아응급진료가 개선됐는지 정량적으로 평가하고자 본 연구를 수행했다.

대상과 방법

2019년 1월 1일에서 2023년 12월 31일 동안 충북대학교병원 응급실을 방문한 소아환자(< 19세) 대상으로, 국가응급환자진료정보망으로 전송하는 병원자료에 기반한 후향적 관찰연구를 시행했다. 본원은 권역응급의료센터로, 연간 약 10,000명의 소아환자가 방문한다. 원내 임상시험연구소의 윤리심의위원회의 검토와 심의를 완료했고 동의서 취득은 면제됐다(IRB no. 2024-03-004).

2019년 1월 1일-2021년 1월 31일을 “도입 전 기간”으로, 2021년 6월 1일-2023년 12월 31일을 “도입 후 기간”으로 각각 정의했다. 전담전문의는 소아청소년과 전문의로 2021년 3월부터 차례로 채용되어 같은 해 5월부터 5인 체제로 근무했기에, 2021년 2월 1일-5월 31일을 중간 기간(interim period)으로 정의했다. 도입 전 기간(전담전문의 채용 전)에는 응급의학과 의사가 초진 후 소아청소년과 전공의가 협진했고, 도입 후 기간에는 전담전문의가 모든 소아응급진료를 담당했다.

수집한 변수는 나이(< 1세, 2-4세, 5-9세, 10-14세, 15-18세), 성별, 응급실 방문 시기(계절, 주말[토·일], 일시[야간: 18-09시]) 및 퇴실 일시(야간: 18-09시), 질병 또는 손상 여부, 외부병원 경유 방문, 119구급차 이용, 응급증상(응급의료에 관한 법률 제2조 제1호 관련 “응급증상 및 이에 준하는 증상”) 해당 여부, 한국형 응급환자 분류도구(Korean Triage and Acuity Scale, KTAS(8)) 및 의식수준(AVPU [alert, verbal, pain, unresponsive] 척도), 증상 발생-응급실 도착 소요 시간, 응급실 체류시간, 응급진료 결과(전체 및 중환자실 입원, 병원내 사망, 재방문[≤ 24시간]), 응급실 방문 시 기재된 한국표준질병사인분류에 따른 주진단이다(9).

도입 전후 기간으로 구분하여 상기 임상적 특징을 비교했으며, 범주형 변수는 수 및 백분율로, 연속형 변수는 중앙값 및 사분위수로 표시했다. 범주형 변수에 대해서는 Pearson 카이제곱 검정을, 연속형 변수에 대해서는 Wilcoxon rank sum 검정을 각각 사용했다. 전담전문의 진료에 따른 소아응급진료 개선 여부를 파악하기 위해 다변량 로지스틱 회귀분석을 이용하여 보정 교차비 및 95% 신뢰구간을 계산했다. 종속변수는 상기 응급진료 결과 변수 4종으로 정의했다. 두 군 간 유의한 차이가 있는 변수와 임상적 판단으로, 나이, 성별, 응급실 방문 시기(계절 및 주말), 질병 또는 손상 여부, 외부병원 경유 방문, 119구급차 이용, 응급증상 해당 여부, KTAS를 잠재적 교란변수로 사용했다. 통계적 분석에 SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.)를 사용했다.

결과

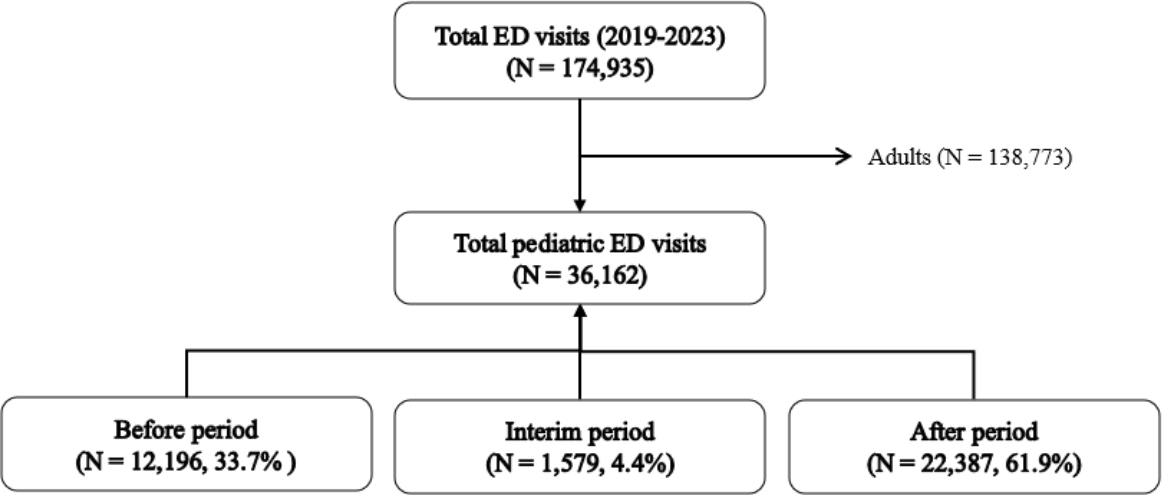

연구기간에 응급실을 방문한 소아환자는 총 36,162명이었으며, 이는 도입 전 기간 12,196명(33.7%), 중간 기간 1,579명(4.4%), 도입 후 기간에는 22,387명(61.9%)으로 이뤄졌다(Fig. 1).

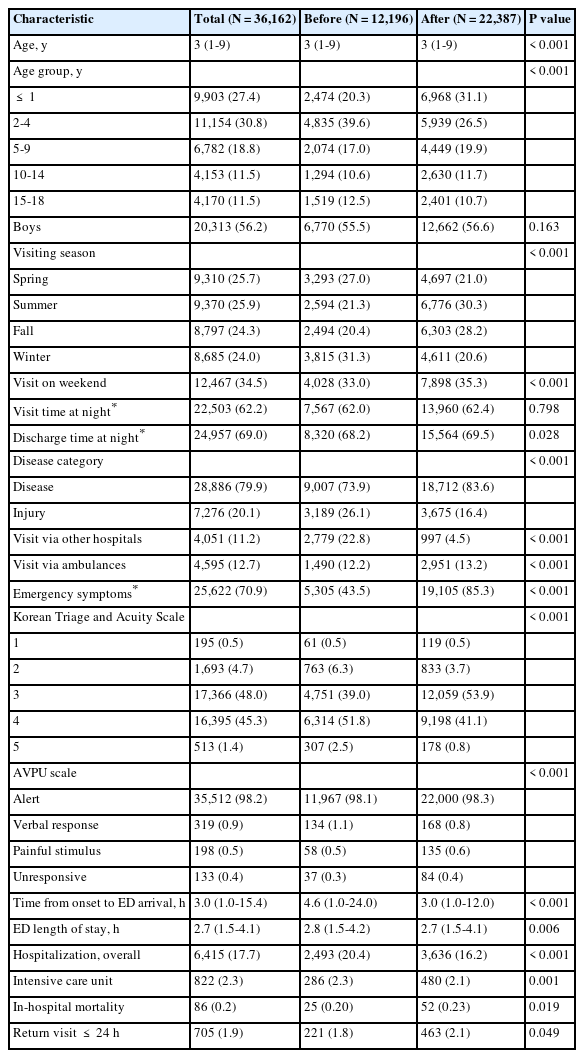

Table 1은 도입 전후 기간에 따른 임상적 특징을 보여준다. 도입 전과 비교하여, 도입 후에 1세 이하 소아환자(20.3% 대 31.1%), 질병(73.9% 대 83.6%), 응급증상(43.5% 대 85.3%)의 빈도가 높았지만, 외부병원 경유의 빈도(22.8% 대 4.5%) 및 응급실 체류시간의 중앙값은 감소했다(2.8시간 대 2.7시간). 응급진료 결과 면에서, 도입 후에 전체 입원이 감소했고(20.4% 대 16.2%), 중환자실 입원도 소폭 감소했다(2.3% 대 2.1%). 병원내 사망은 두 기간 모두 0.2%였고 재방문은 증가했다(1.8% 대 2.1%).

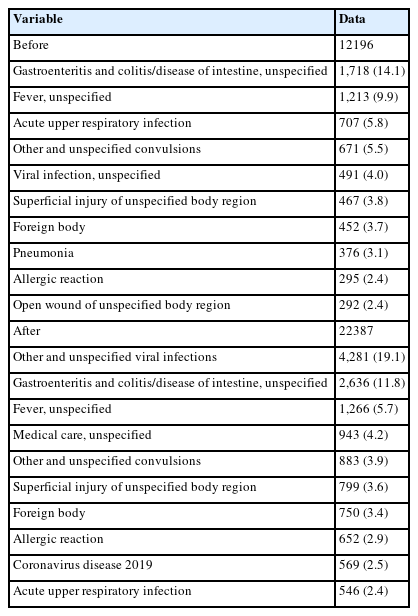

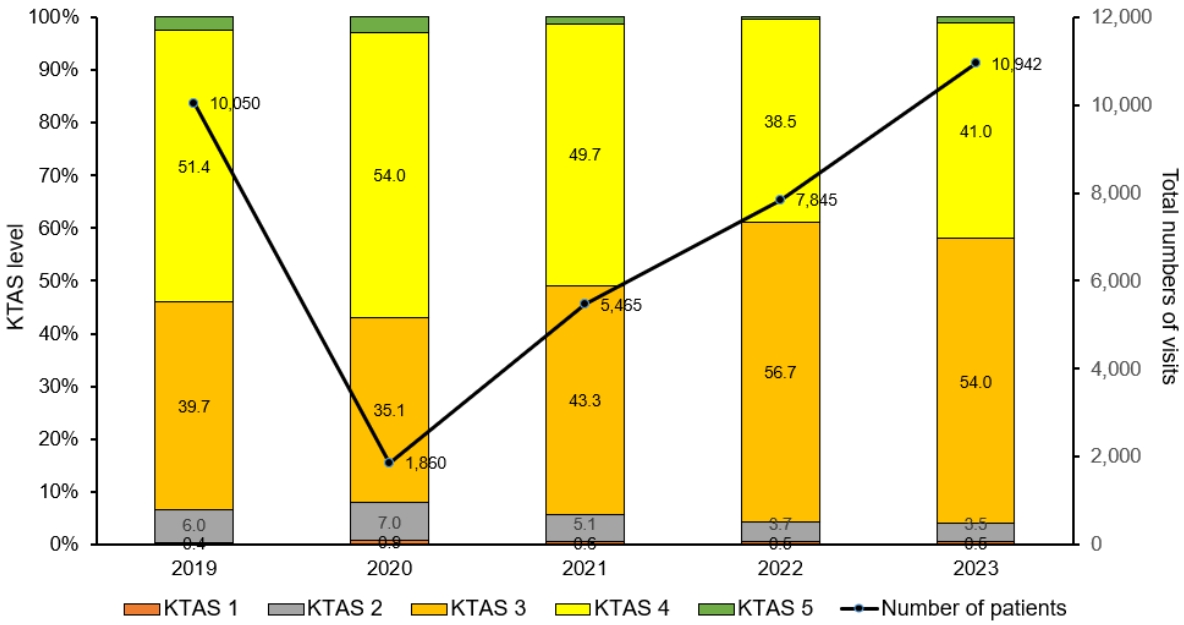

주진단을 비교한 결과, 두 기간 모두 상세 불명의 열, 위장염 및 결장염, 바이러스 감염 등 감염병이 대부분이었다(Table 2). 연도별 소아환자 방문은 2020년 급감한 이후 꾸준히 증가하여 2023년 기준 10,942명이었다(Fig. 2). KTAS 3단계 비율은 2022년까지 점차 증가했으나(56.7%), KTAS 2의 비율은 2020년 7.0%에서 2023년 3.5%로 감소했다.

Annual trend of KTAS levels and total numbers of children’s visits to the emergency department. KTAS: Korean Triage and Acuity Scale.

로지스틱 회귀분석 결과, 도입 후 기간에 전체 입원율은 33% (보정 교차비, 0.67; 95% 신뢰구간, 0.62-0.72), 재방문율은 27% (0.73; 0.61-0.88)였다(Table 3). 중환자실 입원율은 190% 증가했으나, 병원내 사망률은 유의한 차이가 없었다.

고찰

본 연구는 전담전문의 진료 도입에 따라, 소아응급진료가 개선됐음을 보여준다. 전담전문의 도입 이후 소아환자 방문이 83.6% 증가했지만(12,196명 대 22,387명), 전체 입원율 및 응급실 재방문율은 감소했고, 중환자실 입원율은 증가했으나 병원내 사망률은 차이가 없었다.

본원은 권역응급의료센터지만, 연구기간에 소아전용 응급실 또는 전문센터를 운영하지 않았다. 그러나 2024년 1월 전문센터로 선정되어 센터 운영을 준비하기 위해, 본 연구 결과를 타 병원에서 운영 중인 소아전용 응급실 및 전문센터에서 보고한 결과와 비교했다. 전담전문의 진료 도입 이후 1세 이하 방문, 주말 방문, 손상보다는 질병으로 인한 방문이 증가한 것은 선행 연구와 유사하다(5,10). 연구기간에 KTAS 3단계 비율은 점차 증가했으나, 2단계 및 외부병원 경유 방문은 감소했다. 2단계 비율 감소는 본원 소재지와 가까운 천안에 소아전용 응급실(2010년)이, 세종에 전문센터(2023년)가 각각 개소한 후 중증 환자가 일부 분산된 것에 기인한 것으로 추정한다. 3단계 비율 증가는 다수의 경증 환자가 방문한 결과로 해석할 수 있다. 이는 한국의 소아전용 응급실 6개소의 외부 병원을 경유하여 방문한 비율 및 중증 비율이 일반 응급실 132개소보다 모두 낮은 것과 일맥상통한다(10).

전담전문의 진료 도입에 따른 고무적 영향은, 소아환자 방문이 증가했으나 응급실 체류시간은 짧아지고 입원율이 33% 감소했다는 점이다. 2020년 소아환자의 급격한 감소(Fig. 2)는 코로나바이러스병-19 범유행의 영향으로 보이며, 이후 점차 증가하여 2023년에는 2019년도와 비슷한 수준으로 회복했다. 그렇지만 재방문율은 감소하고 병원내 사망률은 두 기간 사이에 유의한 차이가 없어, 양질의 진료를 제공했다고 할 수 있다. 응급실 체류시간 감소는 전담전문의의 높은 진료 수준 자체에 기인했을 수 있다. 그 외에도, 초진 후 소아청소년과 전공의에게 협진을 의뢰하는 기존 방식에서 전담전문의가 직접 입원 결정하는 방식으로 개선되면서, 체류시간 단축에 큰 영향을 미쳤을 것으로 보인다. 선행 연구에서도 전담전문의에 의한 소아진료가 응급실 체류시간 및 사망률 감소 효과가 있음을 보고했다(6,11).

이처럼 전담전문의의 필요성이 대두되고 있기에, 소아응급의학 세부전문의를 포함한 전문 인력을 계속 양성해야 한다(12). 소아응급의학 세부전문의는 소아청소년과학 및 응급의학을 모두 책임질 수 있는 전문 인력이다. 소아청소년과 전공의 급감으로 인해 소아응급진료를 소아청소년과 의사에게 의존하기 어려워지는 환경에서, 응급진료 전문가인 응급의학과 전문의가 상기 세부전문의를 추가 취득하여 소아응급진료를 제공하는 것이 바람직하다.

전담전문의에 의한 소아전용 응급실 운영은 앞서 기술한 이점을 가져다줄 수 있으나, 원래 목적에 따라 운영되지 못하고 있다. 소아전용 응급실 및 전문센터를 이용하는 소아환자는 경증 비율이 높고 하루 평균 방문 및 입원 건수가 현저히 많은 데 반해 입원 후 체류시간이 더 길게 나타나는데, 이는 응급실 과밀화의 악화를 시사한다(10,13). 전문센터가 본연의 역할을 수행하기 위해서는 경증 환자로 인한 과밀화를 억제해야 한다. 전문센터는 수도권 또는 대형 병원에 위치하므로, 이를 이용하기 어려운 지역에 거주하는 소아환자의 전문센터 접근성을 높일 수 있는 다양한 전략이 필요하다. 달빛어린이병원과 같은 1차 의료기관의 역할을 강화하고 경증 환자 대상 상담 서비스를 활성화하여, 불필요한 응급실 이용을 최소화해야 한다. 경증 환자를 담당할 수 있는 소아인증 응급의료센터 신설도 고려할 수 있다(14).

본 연구의 제한점은 다음과 같다. 첫째, 후향적 관찰연구로 노출변수 및 결과변수에 영향을 미치는 잠재적 교란변수가 있을 수 있다. 둘째, 단일 응급실을 방문한 소아환자를 대상으로 연구를 진행하여 결과를 일반화하기 어려울 수 있다. 셋째, 표본 크기로 인한 1종 오류가 발생할 수 있어 주의하여 해석해야 한다. 넷째, 연구기간에 코로나바이러스병-19 범유행이 초래한 소아환자의 응급실 방문 및 진료 양상의 변화가 결과에 미친 영향을 분석하지 못했다.

결론적으로, 본원은 전담전문의 진료 도입 이후 지역 내 발생하는 소아환자를 대상으로 양질의 진료를 제공했다. 구체적으로, 소아환자 증가에도 불구하고 전체 입원율 및 응급실 재방문율은 감소했고, 중환자실 입원율은 증가했으나 병원내 사망률은 차이가 없었다. 향후 전담전문의 위주의 소아응급진료를 지속하기 위해 다방면으로 노력해야 한다.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, and Visualization: BH Kim and GJ Park

Data curation and Validation: GJ Park and SC Kim

Project administration: GJ Park

Resources: BH Kim, YM Kim, and HS Chai

Supervision: H Kim and SW Lee

Writing-original draft: BH Kim and GJ Park

Writing-review and editing: YM Kim, HS Chai, SC Kim, H Kim, and SW Lee

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Funding sources

No funding source relevant to this article was reported.