만삭 영아에서 진단된 자궁과 양측 자궁부속기의 서혜탈장

Inguinal hernia containing the uterus and both adnexa in a full-term infant

Article information

Trans Abstract

We report a case of inguinal hernia that contained the entire uterus and both adnexa, presenting with an irreducible soft mass in the left groin and asymmetric labia majora, in a 2-month-old, full-term girl who visited the emergency department. Ultrasonography was performed immediately, and urgent surgical repair was performed without complications. Although inguinal hernia is a common surgical disease, it is rare that the hernia contains the uterus with its adnexa, and presents as a mass of the labia majora. Unlike the bowel herniation, the entity can be complicated by strangulation of the ovary, leading to infertility. To preserve fertility, rapid and accurate diagnosis using ultrasonography should be considered in an infant with an irreducible inguinal mass and asymmetric labia majora.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia is common, chiefly in infants. The cumulative incidences of hernia repair in the first 7 years of life are 9.0% and 4.1% in children with and without history of preterm birth, respectively[1]. Although boys are affected about 4 times more frequently than girls, girls are at a higher risk of incarceration[1-3]. Although the hernia contains the ovary and occasionally the fallopian tube in about 15% of female infants[4], the hernia containing the uterus has rarely been reported. Akillioglu et al.[5] showed that only 7 of the 3,100 girls (0.2%) with inguinal hernia contained the uteri in their hernia sacs. Thus, inguinal hernia containing both uterus and adnexa may be exceptionally rare, and only 2 cases have been reported in premature infants[6,7], but not in full-term infants.

We report a case of inguinal hernia containing the entire uterus and both adnexa in a full-term infant who visited the emergency department with an irreducible mass in the left groin and asymmetric labia majora. The institutional review board of Asan Medical Center approved this study (IRB no. 2021-0851).

Case

A 2-month-old girl visited the emergency department with a painless soft mass in the left groin and asymmetric labia majora. The mass was noticed by her mother without overlying erythema on it and tenderness in the left groin 3 days prior to the visit. The size of the mass had not changed until the visit. No other symptoms, such as vomiting, constipation, irritability or pain, developed. The girl was delivered at the postconceptional age of 40 1/7 weeks with the birth weight of 3,020 g. She had no significant medical history.

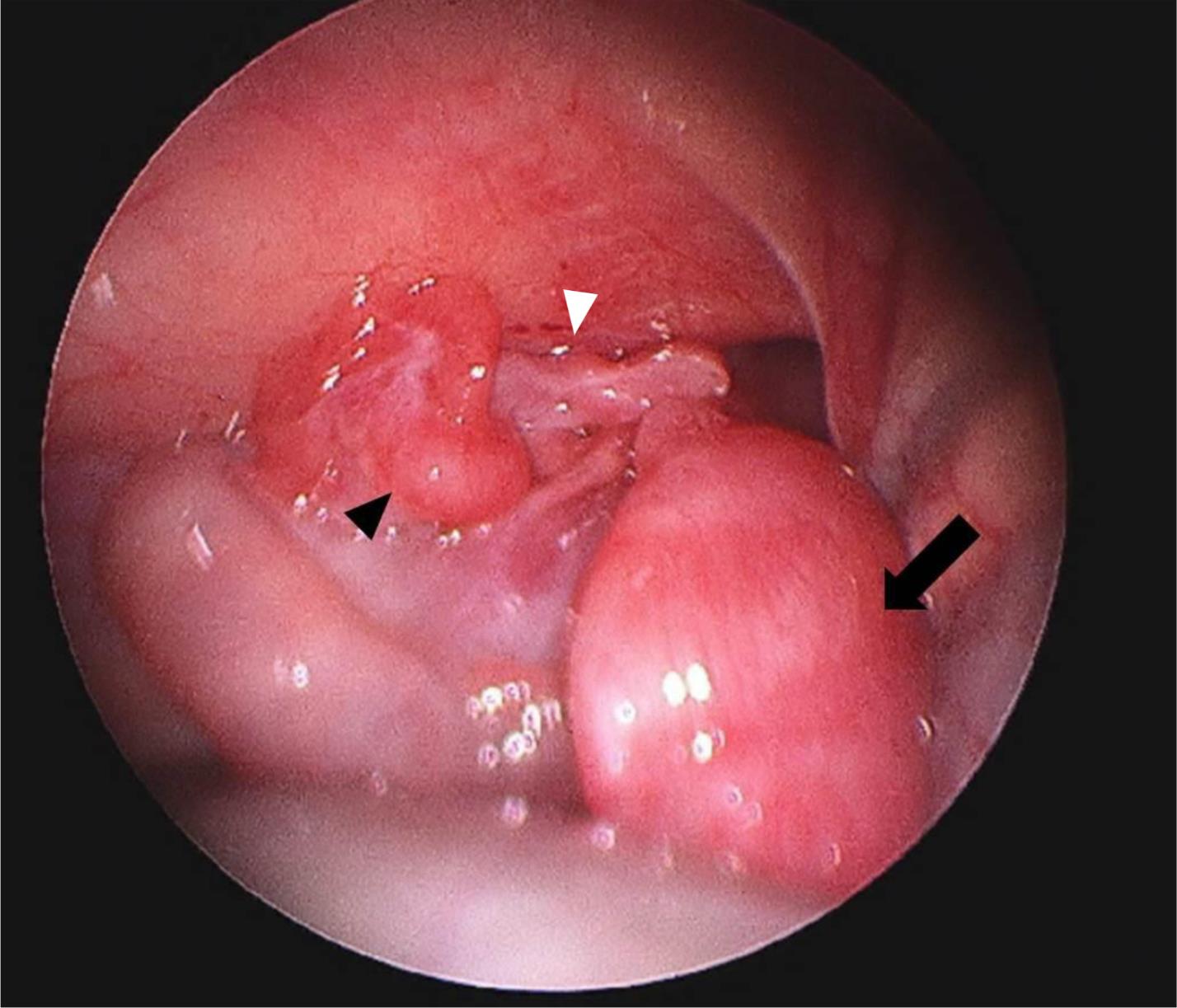

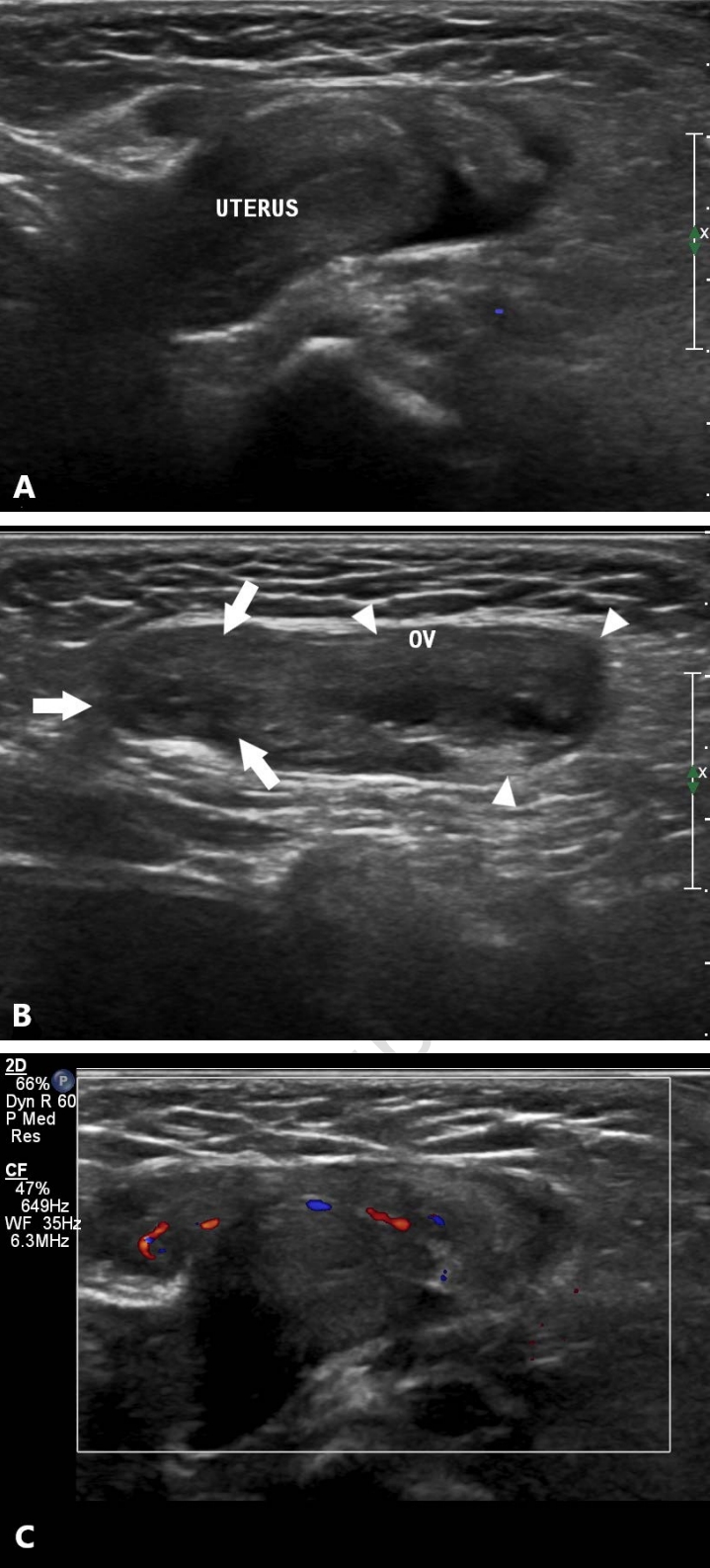

The initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 91/64 mmHg; heart rate, 166 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths per minute; temperature, 36.3°C; and oxyhemoglobin saturation, 99%. Her mass spanned from the left inguinal area to the labia majora (Fig. 1). No genital anomalies were noted. An initial attempt to reduce the mass was unsuccessful, suggesting an incarcerated hernia. Ultrasonography (US) using iE33 (Philips Ultrasound, Bothell, WA) with a 5- to 12-MHz linear transducer showed the herniation of the uterine body and fundus, both tubes, and the ovaries without a sign of strangulation (Fig. 2). She was immediately hospitalized for surgical observation. On day 2, 4 days after the symptom onset, laparoscopic hernia repair was performed. The herniated organs, which appeared edematous but well-perfused, were gently returned to the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 3). High ligation of the hernia sac was performed without complications. On day 3, the girl was discharged uneventfully.

A 4-cm-sized, sausage-shaped left inguinal mass and the asymmetrically swollen labia majora (arrows).

Transverse scans showing (A) the herniated uterine fundus and (B) ovary (OV, arrows and arrowheads) through the canal of Nuck. (C) Preserved vascularity of the ovary is noted from a Doppler image.

Discussion

This article presents an infant with an irreducible mass in the left groin and labia majora, which was caused by the herniated uterus and both adnexa, suggesting the need for prompt US to distinguish the unusual contents of hernia.

Among the causes of inguinal masses, hernia is the most common diagnosis[3,8]. Indirect hernia, which accounts for 95% of inguinal hernia, is caused by the patent processus vaginalis, an evagination of the parietal peritoneum, which develops at 12 weeks of gestation[9]. Given that this structure typically closes at 7 months of gestation in girls, the patent processus vaginalis is also called the canal of Nuck[9]. It spans from the uterus to the labia majora, allowing the development of indirect hernia[10].

Inguinal hernia usually presents with a soft, painless mass around the groin, labia or scrotum. Among these regions, an asymmetric labia majora with mass, as in the case patient, may be pathognomonic for ovarian involvement[11], which is implied by an irreducible hernia in girls[12]. Inguinal hernia with suspected ovarian involvement should be evaluated immediately. Unlike other hernias, those containing the adnexa rarely regress spontaneously and carry a greater risk of incarceration because the ovary is larger than the vascular pedicle. Specifically, girls are at a higher risk of incarceration than boys (29% vs. 12%)[3]. Hence, surgical repair within 24-48 hours is required to prevent torsion[3,12,13]. No specific time interval is predictive of ovarian necrosis. In an observational study on 22 children with ovarian torsion, 6 with the salvaged ovaries had a mean time of 87 hours (range 7-159) from symptom onset to surgical evaluation[14]. Therefore, US should be performed promptly to differentiate contents of inguinal mass, and rule out other diagnoses, such as hydrocele, congenital labial cyst or Bartholin’s gland cyst[8]. For this differential diagnosis, US is recommended with a 100% accuracy in distinguishing an inguinal hernia containing the ovary from a hydrocele in the labia majora[11].

Inguinal hernia containing the uterus was reported in several disorders of sex development with the male phenotype, but rarely in a normal female karyotype and phenotype[5,7]. In our case, no chromosomal study was performed because of the normal appearance of the external genitalia and internal reproductive organs. Despite the unclear pathophysiology of hernia containing the uterus, it has been suggested that the elongated uterine suspensory ligaments are involved[6].

In summary, a female infant presenting with an irreducible inguinal mass and asymmetric labia majora may have a hernia containing the uterine adnexa and even the uterus. With this entity in consideration, rapid diagnosis using US and prompt management should be performed to preserve fertility from a possible incarceration of the ovary.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Acknowledgements

No funding source relevant to this article was reported.