2형 당뇨병을 처음 진단받은 14세 여자 환자에서 발생한 좌측 넓적다리동맥의 의인 혈전증을 동반한 당뇨병케토산증 및 고삼투질비케토산혼수 증례

A case of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state complicated with iatrogenic left femoral arterial thrombosis in a 14-year-old girl with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus

Article information

Trans Abstract

Although diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality of type 1 diabetes mellitus, DKA also occurs in ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes. Recently, cases of DKA associated with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) have been reported in adolescents. We reported a 14-year-old girl with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus-associated DKA and HHS complicated with iatrogenic left femoral arterial thrombosis, requiring a below-knee amputation. In DKA and HHS, risk factors for thrombosis, vascular access predisposes patients to thrombosis. Consequently, occurrence of thrombosis should be monitored in patients with DKA or HHS.

Introduction

While diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality of type 1 diabetes mellitus, recent studies have shown that 12%-56% of DKA cases occur in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[1]. Such cases are usually characterized by obese patients with family history of T2DM who show severe hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. This specific form is termed ketosis-prone T2DM[2].

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) has high mortality and morbidity rates in elderly patients with T2DM, of which mortality is approximately 10 times higher than that of DKA[3]. Recently, pediatric cases of DKA associated with HHS have been reported[4]. Several patients with DKA associated with HHS consumed carbohydrate-rich beverage to relieve thirst, worsening their clinical courses[5].

There are some reports of thrombosis as a complication of DKA. Specifically, Keane et al.[6] reported a case of a 5-year-old patient with cerebral venous thrombosis. Worly et al.[7] reported pediatric cases of femoral central venous catheter-associated thrombosis. Several related studies have shown that some pediatric patients with DKA also develop coagulation abnormalities.

In this case report, we described an adolescent girl with newly diagnosed T2DM-associated DKA and HHS who underwent left leg amputation due to a complication of iatrogenic arterial thrombosis. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB no. 2020-08-0009).

Case

A 14-year-old Asian girl visited a local clinic with general weakness, agitation, and sleep disturbance. She had a 2-week history of polyuria, polydipsia, and a 10-kg weight loss over 1 month. At the clinic, the girl was considered to have an acute stress disorder and administered intravenous dextrose and diazepam. Because her mental status had become semicoma within the following day, she was transferred to the emergency department. Further history indicated that she had consumed a large amount of a carbohydrate-rich beverage during the previous 5 days. She had no family history of diabetes.

The initial vital signs were as follows; blood pressure, 60/35 mmHg; heart rate, 115 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 15 breaths per minute; temperature, 38.6°C; and the Glasgow Coma Scale, 5 (eye opening 1, verbal response 1, and motor response 3). The skin was dry with reduced turgor. Her weight, height, and body mass index were 55 kg (50%-75%), 160 cm (50%-75%), and 21.5 kg/m2, respectively.

Initial arterial blood gas findings were as follows: pH, 7.25; PaO2, 115.7 mmHg; PaCO2, 13.0 mmHg; HCO3, 5.5 mmol/L; and base deficit, 18.1 mmol/L. The calculated anion gap was 35.9 mmol/L. Biochemical findings were as follows: serum glucose, 1,265 mg/dL; serum sodium, 160 mmol/L (corrected value, 179 mmol/L); potassium, 4.8 mmol/L; chloride, 122 mmol/L; osmolality, 405 mmol/kg; blood urea nitrogen, 21.3 mmol/L; creatinine, 3.5 mg/dL; C-reactive protein, 19.6 mg/L; insulin, 8.9 pmol/L (reference value, 14-156 pmol/L); and C-peptide, 0.5 nmol/L (reference value, 0.12-1.19 nmol/L). Urine glucose and ketone were 3+.

In the emergency department, endotracheal intubation and intravenous administration of normal saline and inotropes were performed due to respiratory distress and hypotension, respectively. The girl was treated with a continuous insulin infusion at a rate of 0.1 IU/kg/hour. Eventually, she was hospitalized to the intensive care unit.

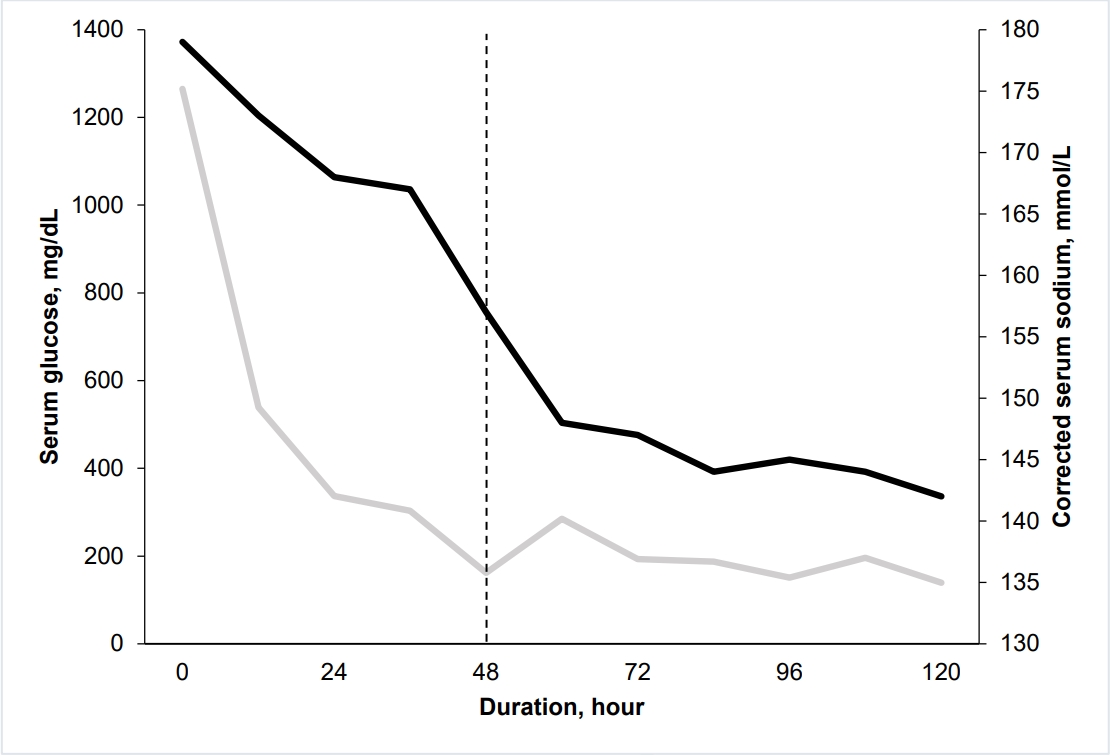

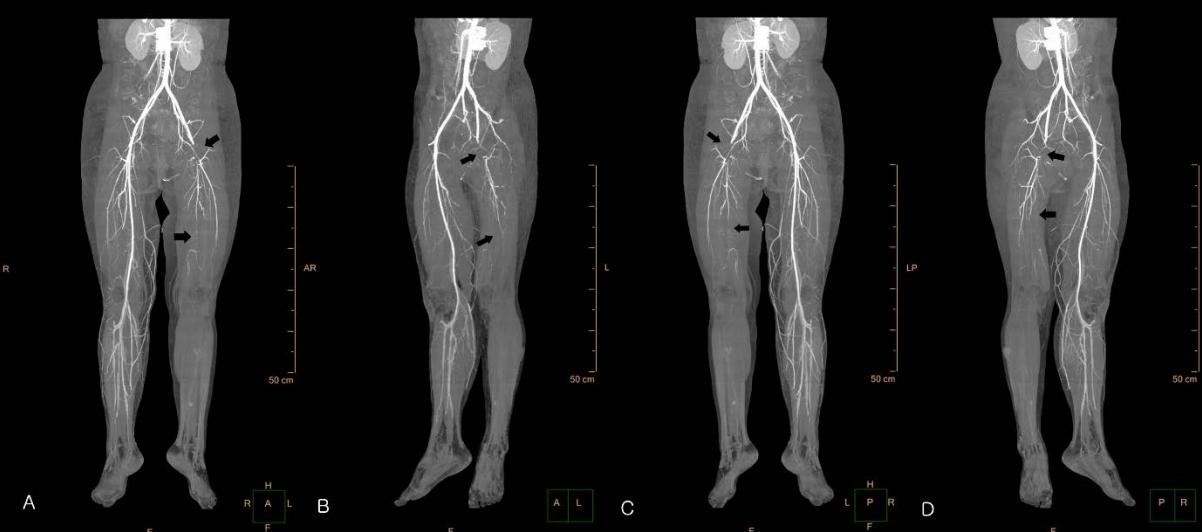

On day 2, she became alert. Her vital signs were stabilized, and the serum glucose concentration improved (Fig. 1). However, a skin color change was observed below the left knee without a palpable pulse of the ipsilateral femoral artery (Fig. 2). The area of color change was below the point of puncture for an arterial line inserted to the left femoral artery on day 1 (29 hours prior to the development of color change). At that time of insertion, a physician noted intact arterial pulse and skin color in the area. Lower extremity computed tomography angiography was immediately performed, confirming a thrombus in the left femoral artery (Fig. 3). Subsequently, she underwent thrombectomy and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Despite the interventions, the left leg could not be saved, and she underwent a below-knee amputation.

Serum glucose (gray line, mg/dL) and corrected serum sodium (black line, mmol/L) concentrations during the first 120 hours. On day 2, the serum glucose concentration improved (dash line).

Lower extremity computed tomography angiography performed on day 2 showing a complete obstruction (arrows) of the left common femoral artery and left superficial femoral artery.

On day 9, continuous insulin infusion was stopped, and subcutaneous long-acting insulin and metformin were started along with oral feeding. On day 29, serum glucose concentration was within the normal range without long-acting insulin. At this point, HbA1c level tested at the time of visit was found to be 12.9%. Assays for glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies, anti-insulin antibodies, and islet cell antibodies were negative. She was discharged after 2 months of rehabilitation. The final diagnosis was T2DM-associated DKA and HHS complicated with iatrogenic left femoral arterial thrombosis.

Discussion

Clinical features of patients with ketosis-prone T2DM include obesity, family history of T2DM, and negative autoimmune antibodies[8]. In patients with DKA associated with HHS, complications of both conditions should be considered[4]. Our case met all criteria for DKA associated with HHS; pH < 7.30, HCO3 < 15 mmol/L, and serum osmolality > 330 mOsm/L[9].

The severe hypernatremia of this case might be due to the prolonged dehydration and osmotic diuresis caused by the ingestion of carbohydrate-rich beverage for 5 days. There have been some reports of DKA associated with hyperosmolarity, hypernatremia, and intake of carbohydrate-rich beverage. When a patient with DKA ingests such a drink, hyperglycemia worsens. Since hyperglycemia incurs osmotic diuresis, free water and electrolytes are lost, resulting in dehydration. If the free water loss is greater than sodium loss, hypernatremia is induced. Most carbohydrate-rich beverage contain a large amount of sodium, which incurs a hyperosmolar and hypernatremic state, as shown in our case[5].

The case patient underwent an iatrogenic arterial thrombosis. A study has shown that patients with DKA and HHS have a 6.8- and 16.3-fold higher risks of thrombosis, respectively, compared to patients with depression[10]. In DKA associated with HHS, predisposing factors for thrombosis include abnormalities of blood volume, blood flow, coagulation factors, platelet activation, and vascular reactivity. DKA is more strongly associated with arterial thrombosis than with venous thrombosis[11]. Fitzgerald et al.[12] reported that in a series of 160 episodes of DKA, 5 of 19 deaths were due to arterial thrombosis. Similarly, Beigelman et al.[13] reported that 11 of 32 deaths were related to arterial thrombosis. The utility of prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with DKA remains unclear[14]. Currently, vascular access to body parts without collateral circulation should be minimized to prevent iatrogenic thrombosis in patients with DKA or HHS.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of an Asian adolescent with DKA and HHS complicated with an iatrogenic arterial thrombotic at the onset of T2DM. Despite the rarity of such cases, the occurrence of thrombosis should be monitored in pediatric patients with DKA or HHS.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Acknowledgements

No funding source relevant to this article was reported.