|

|

AbstractPurposeTriage tools play a vital role in classifying the severity of children in emergency departments (EDs). We investigated the association between the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) and severity of dyspnea in the ED.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective study of children aged 3-14 years with dyspnea who visited the ED from January 2015 through December 2021. They were divided into severe (KTAS level 1-3) and non-severe (KTAS level 4-5) groups. Between the groups, we compared the clinical characteristics, including age, sex, associated symptoms, vital signs, route of visit, treatment at ED, and outcomes.

ResultsAmong a total of 468 children with dyspnea, 267 and 201 were assigned to the severe and non-severe groups, respectively. The severe group had higher frequencies of fever (21.7% vs. 13.9%; P = 0.031), cough (53.2% vs. 43.3%; P = 0.034), systemic steroids (42.3% vs. 25.9%; P < 0.001), intravenous fluids (47.6% vs. 25.4%; P < 0.001), oxygen therapy (16.5% vs. 6.5%; P = 0.001), inotropics (4.1% vs. 1.0%; P = 0.042), and hospitalization (24.7% vs. 11.9%; P = 0.002). The severe group also showed a higher mean heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature, and lower mean oxygen saturation (all Ps < 0.001). Among these findings, fever, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, intravenous fluids, oxygen therapy, inotropics, and hospitalization remained significantly different between the groups after defining the severe group as a KTAS level 1-2.

IntroductionIn emergency departments (EDs), children with dyspnea need emergency measures to prevent developing respiratory failure1). It is vital to classify severity of such children using a triage tool. In Korea, the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) has been used for the purpose since 20162). However, there is a lack of research on applying KTAS to children with dyspnea. Hence, we investigated an association between KTAS and severity of dyspnea in the ED.

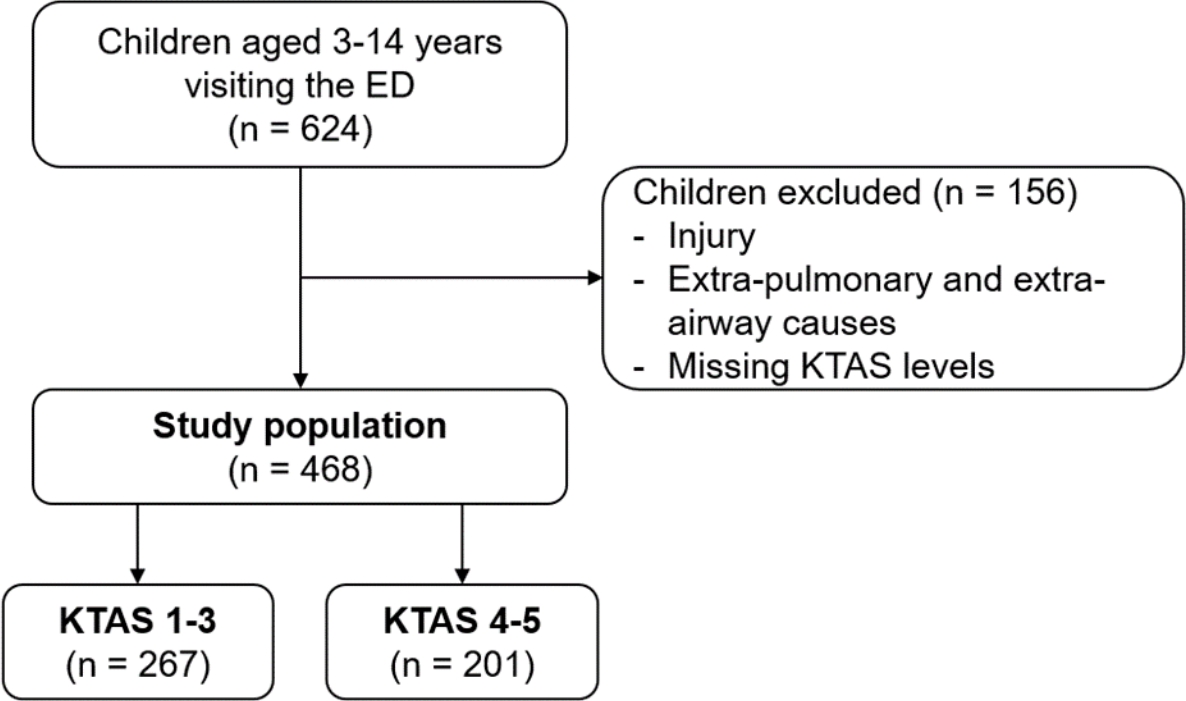

Methods1. Study populationThe study is a single center, retrospective study through a review of medical records from January 2015 through December 2021, at Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital in Uijeongbu, Korea. We included children aged 3-14 years who visited the ED with dyspnea as a main symptom. Exclusion criteria were injury, extra-pulmonary and extra-airway diseases, and missing KTAS levels. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the hospital with a waiver of informed consent (IRB no. UC22RASI0070).

2. Data collectionTo assess the association between KTAS and severity of dyspnea, we compared the following variables between the severe and non-severe groups. The variables included the age (years), sex, initial KTAS level, associated symptoms (e.g., fever [≥ 37.5℃], cough, and sputum), heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, altered mentality (levels of consciousness other than alertness), route of visit (direct, outpatient department, and transfer), and treatment at ED (e.g., nebulization, systemic steroids, and intravenous [IV] fluids). Outcomes included discharge, hospitalization, length of hospital stay (day), and transfer. Additionally, a return visit within 7 days of the index visit was analyzed. Of these outcomes, hospitalization was sought as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation.

The KTAS level was determined at triage by nurses who had more than 1 year of clinical experience in the ED and completed a KTAS training hosted by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Society of Emergency Medicine. According to the KTAS level, the study population was divided into severe (level 1-3) and non-severe (level 4-5) groups. A priori sensitivity analysis was carried out to confirm the abovementioned association by additionally defining the severe group as KTAS level 1-2.

3. Statistical analysisFor continuous variables, Student t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests were used. For categorized variables, chi-square tests were used to analyze the difference between the groups. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were done by IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, ver. 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results1. Baseline characteristicsAmong a total of 624 children aged 3-14 years with dyspnea who visited the ED, 468 were included in the study after the exclusion of 156 children. The study population was divided into the severe (n = 267) and non-severe (n = 201) groups (Fig. 1).

The study population had a mean age of 7.7 years, and a proportion of boys was 71.6% (Table 1). The main associated symptoms were cough (48.9%), rhinorrhea (25.9%), and sputum (25.4%). Fever was reported in 18.4%. No children reported drooling, dysarthria, dysphasia, grunting, hemoptysis, nasal flaring or pallor. Most children directly visited the ED (90.4%). Nebulization, systemic steroids, and IV fluids were performed or administered in 72.0%, 35.3%, and 38.0%, respectively. The frequency of hospitalization rate was 19.2%. Of the 375 discharged children, 90 (24.0%) were administered IV fluids.

2. Comparison of the characteristics according to the KTAS levelsFever and cough were more frequently reported in the severe group (Table 2). In this group, the mean values of heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature were higher than in the other group. Also, oxygen saturation was lower in the severe group. Of the treatments at ED, systemic steroids, IV fluids, oxygen, and inotropics were more frequently administered in the severe group. In this group, nebulization tended to be used more often, but the difference was not significant. The children in the severe group showed a higher frequency of hospitalization (24.7% vs. 11.9%; P = 0.002), and discharge after IV hydration (30.7% vs. 16.5%) than those in the non-severe group.

The sensitivity analysis showed that the differences in the proportions of fever, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, IV fluids, oxygen therapy, inotropics, and hospitalization remained significant after the sensitivity analysis (Table 3).

DiscussionThis study shows the association between KTAS and severity of dyspnea in the ED. The association is supported by the higher frequencies of fever, cough, systemic steroids, IV fluids, oxygen therapy, inotropics, and hospitalization, higher mean values of heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and lower mean value of oxygen saturation in the severe group. Among the significant findings, fever, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, IV fluids, oxygen therapy, inotropics, and hospitalization remained significantly different between the groups after the sensitivity analysis. Hence, KTAS may reflect not only the initial clinical conditions but also emergency measures and outcomes in children with dyspnea who visit EDs.

The study shows that fever was associated with KTAS levels in the children with dyspnea. In the state of respiratory distress, fever suggests a possible respiratory tract infection. Thus, fever should be considered when classifying the children using KTAS in EDs.

Many study children had cough, rhinorrhea, and sputum as the associated symptoms. Among the symptoms, cough was most common and associated with the severity classified by KTAS. However, in this classification, only primary symptoms were considered. As per a study regarding the association between the KTAS and abdominal pain-related hospitalization, vomiting and fever were respectively less and more commonly associated symptoms in children who were classified KTAS 1-3 than those who were done KTAS 4-53). Associated symptoms should be additionally considered a classification factor to improve the accuracy of KTAS. The symptoms may be particularly useful in triaging children who are too young to express their symptoms in languages, show nonspecific symptoms or vary in ranges of vital signs per age group.

The study also showed that in the severe group, IV fluids, oxygen, and inotropics were more frequently administered. Indeed, oxygen therapy is a crucial conservative measure of bronchiolitis4). Also, steroids can be used to minimize the severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome by weakening the immune and inflammatory systems5-7). Although nebulization was applied to 72.0% of the study population, there was no difference in the frequency between the groups. This finding suggests that nebulization might have been unnecessarily applied to some children. The redundant nebulization could increase a length of stay in EDs. At triage, the need for nebulization should be assessed.

The study has some limitations. First, the single center setting and exclusion of children younger than 3 years indicate a limited applicability to entire pediatric population, particularly infants or toddlers. Second, we did not analyze the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on the characteristics of the children who visited the ED in 2020-2021. Finally, if characteristics, such as fever or altered mentality, had already been considered in the triage, it may have led to circular argument errors. Although it is desirable to investigate each characteristic at each KTAS level, the small number of the children with KTAS level 1-2 was insufficient for statistical analysis.

In conclusion, KTAS is considered an appropriate triage tool that reflects the severity of dyspnea in children who visit EDs. In addition, if the associated symptoms are considered together, it will be of practical help in the initial triage of the children. To improve emergency care for children with dyspnea, it is necessary to continuously assess and revise KTAS application in children.

Fig. 1.Flowchart for the selection of study population. ED: emergency department, KTAS: Korean Triage and Acuity Scale.

Table 1.Baseline characteristics

Table 2.Comparison of the characteristics according to the KTAS levels

Table 3.Sensitivity analysis

References1. Choi SJ, Yoon HS, Yoon JS. Respiratory distress in children and adolescents. J Korean Med Assoc 2014;57:685–92. Korean.

2. Park J, Lim T. Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS). J Korean Soc Emerg Med 2017;28:547–51. Korean.

3. Kim S, Woo SH, Choi KH, Oh YM, Choi SM, Kyong YY. Association between the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale level and hospitalization of children with abdominal pain in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Med J 2017;4:97–101. Korean.

4. Da Dalt L, Bressan S, Martinolli F, Perilongo G, Baraldi E. Treatment of bronchiolitis: state of the art. Early Hum Dev 2013;89 Suppl 1:S31–6.

5. Hon KL, Leung KKY, Oberender F, Leung AK. Paediatrics: how to manage acute respiratory distress syndrome. Drugs Context 2021;10:2021–1. -9.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|