|

|

AbstractPurposeDiagnosis of anaphylaxis depends on clinical manifestations and a high index of suspicion, and a misdiagnosis can lead to a preventable death. We aimed to investigate age group characteristics of clinical features and epinephrine use in children with anaphylaxis who visited the emergency department (ED).

MethodsWe performed a retrospective chart review of 138 children who visited a tertiary care hospital ED from January through December 2018, and were discharged with anaphylaxis as the diagnosis. Anaphylaxis was defined according to the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease criteria. The children were divided into 4 age groups; infants (< 1 year), preschoolers (1-5 years), schoolers (6-11 years), and adolescents (12-18 years). Clinical features and epinephrine use were compared among the age groups.

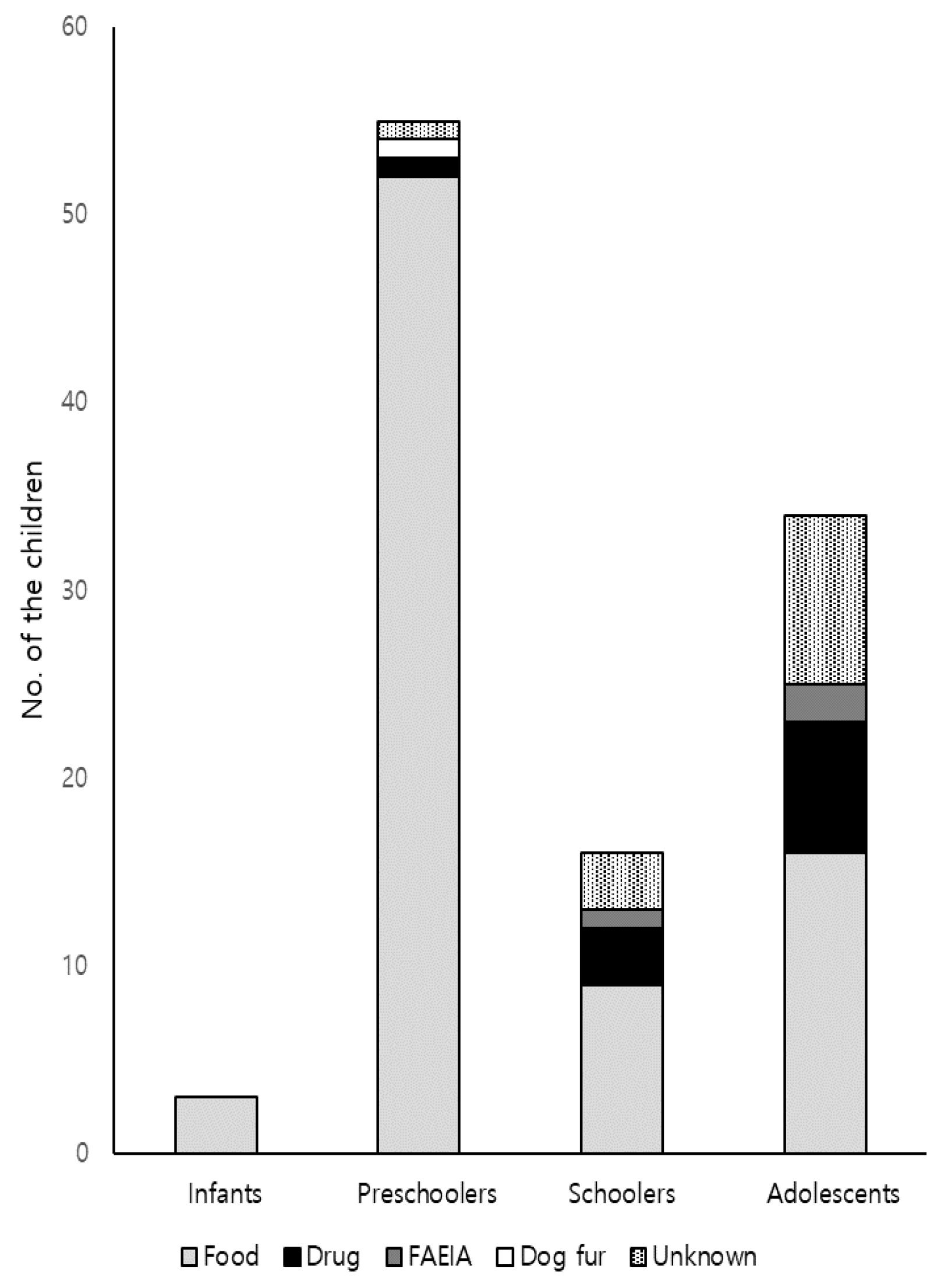

ResultsOf the 138 children with presumed anaphylaxis, 108 met the criteria. The most common cause was food (74%), followed by drugs (10.2%). Epinephrine was used in 82 children (75.9%). The infants and preschoolers reported less frequent cardiovascular symptoms (0%-3.6% vs. 26.5%, P = 0.020) and epinephrine use (33.3%-70.9% vs. 91.2%, P = 0.037) compared to the adolescents. The former 2 age groups reported food as triggers more frequent, and often reported food-associated and respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms.

ņä£ļĪĀņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ļŖö ņÖĖļČĆ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļ®┤ņŚŁļ░śņØæņØä ņØ╝ņ╗½ļŖöļŹ░, ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ ņżæņŚÉņä£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļŖö ņżæņ”Ø ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ ļ░śņØæņØ┤ Ēö╝ļČĆ, ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│ä ņ£äņןĻ┤ĆĻ│ä, ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│äņŚÉ ļÅÖņŗ£ļŗżļ░£ņĀüņØĖ ĻĖēņä▒ ņ”ØņāüņØä ņØ╝ņ£╝ĒéżļŖö ņ¦łĒÖśņ£╝ļĪ£, ņ╣śļŻīĒĢśņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢśļ®┤ ņé¼ļ¦ØņŚÉ ņØ┤ļź╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[1,2]. ņäĖĻ│äņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ļ░£ņāØļźĀņØĆ ļ¬ģĒÖĢĒĢśĻ▓ī ņĢīļĀżņ¦Ćņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŖöļŹ░, ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ│╝Ļ▒░ņŚÉ ņ¦äļŗ© ĻĖ░ņżĆņØ┤ ļ¬ģĒÖĢĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśĻ│Ā ņØśļŻīņ¦äņØ┤ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļź╝ ņĀ£ļīĆļĪ£ ņØĖņ¦ĆĒĢśņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŗżņĀ£ļ│┤ļŗż ņĀüĻ▓ī ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä Ē¢łĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļŗż. Ļ│╝Ļ▒░ ņØīņŗØ ļśÉļŖö ņĢĮ ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ņØś ņØ╝ņóģņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāØĻ░üĒ¢łļŗżĻ░Ć, 2006ļģäĻ│╝ 2011ļģäņŚÉ ņāłļĪŁĻ▓ī ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ¦äļŗ© ĻĖ░ņżĆ ļ░Å ņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©[1,3]ņØ┤ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉśļ®┤ņä£ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ ņĀÉņĀÉ ļŖśņ¢┤ļéśļŖö ņČöņäĖņØ┤ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļ╣äĒŖ╣ņØ┤ņĀü ņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤Ļ▒░ļéś ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ņŚåņ£╝ļ®┤ ņ×äņāü ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ļåōņ╣Ā ņłś ņ׳ņ¢┤[4], ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ļ░Ć ļŖ”ņ¢┤ņĀĖ ņśłĒøäĻ░Ć ļéśļ╣Āņ¦ł ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[5,6]. ĒŖ╣Ē׳ 1-5ņäĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ļŗżļźĖ ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│┤ļŗż ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżĻ░Ć ĒØöĒĢśĻ│Ā ļ│┤ņ▒ö, ņØīņŗØ Ļ▒░ļČĆ, ĻĄ¼ĒåĀ ļō▒ ļ╣äĒŖ╣ņØ┤ņĀü ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ĒØöĒĢśĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņ×äņāü ņ¢æņāüņØś ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│ä ĒŖ╣ņ¦ĢņØ┤ ņ¦äļŗ©Ļ│╝ ņ╣śļŻīņŚÉ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż[7]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ĒĢ£ĻĄŁņŚÉņäĀ ņåīņĢä ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×É ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ļČĆņĪ▒ĒĢ£ ņŗżņĀĢņØ┤ļŗż[8-10].

ļ│Ė ņĀĆņ×ÉļŖö ļŗ©ņØ╝ ņØæĻĖēņØśļŻīņä╝Ēä░ņŚÉ ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ 18ņäĖ ņØ┤ĒĢś ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ×äņāüņ”Øņāü ļ░Å ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØś ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│ä ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØä ļČäņäØĒĢśĻ│Āņ×É ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒ¢łļŗż.

ļīĆņāüĻ│╝ ļ░®ļ▓Ģ1. ļīĆņāü2018ļģä 1-12ņøöņŚÉ ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ņä£ņÜĖņØś ļŗ©ņØ╝ ņØæĻĖēņØśļŻīņä╝Ēä░ ņØæĻĖēņŗżļĪ£ ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ 18ņäĖ ņØ┤ĒĢś ĒÖśņ×É ņżæ Ēć┤ņŗżņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżņØĖ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ē¢łļŗż. ĻĄŁņĀ£ņ¦łļ│æļČäļźś 10ĒīÉ(International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision)ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ¦äļŗ© ņĮöļō£(T50.9, T63.0, T63.1, T63.2, T63.3, T63.4, T63.5, T63.6, T63.9, T78.0, T78.2, T80.5, T88.6, Y57.9)ļĪ£ Ļ▓ĆņāēĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņĀäņ×ÉņØśļ¼┤ĻĖ░ļĪØņØä ĒøäĒ¢źņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäņäØĒ¢łļŗż. ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļ│ĖņøÉ ņ×äņāüņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŗ¼ņØśņ£äņøÉĒÜīņØś ņŖ╣ņØĖņØä ņ¢╗Ļ│Ā ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒ¢łļŗż(IRB No. 2019-0771).

2. ņ¦äļŗ©ĻĖ░ņżĆņāüĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņĀäņ×ÉņØśļ¼┤ĻĖ░ļĪØņØä ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ 2006ļģä National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium[1]Ļ│╝ 2011ļģä World Allergy Organization[2]ņŚÉņä£ ļ░£Ēæ£ĒĢ£ ņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØś ņĀĢņØśņŚÉ ņżĆĒĢśņŚ¼, ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ĒÖĢņØĖĒ¢łļŗż. ĻĄ¼ņ▓┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£, ņäĖ ĻĖ░ņżĆ ņżæ ĒĢśļéś ņØ┤ņāüņØä ņČ®ņĪ▒ĒĢśļ®┤ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļĪ£ ņĀĢņØśĒ¢łļŗż(Table 1).

3. ņ×ÉļŻīņłśņ¦æĒæ£ņżĆĒÖöļÉ£ ņ”ØļĪĆļ│┤Ļ│Āņ¢æņŗØņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņØæĻĖēņŗż ļ░®ļ¼Ė ļŗ╣ņŗ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņä▒ļ│ä, ļéśņØ┤, ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ ļ░Å ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż Ļ│╝Ļ▒░ļĀź, ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł, ņ”Øņāü, ņ┤łĻĖ░ ĒÖ£ļĀźņ¦ĢĒøä, ņ╣śļŻīļ░®ļ▓Ģ(ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ® ĒżĒĢ©), ņ×ģņøÉ, ņżæĒÖśņ×Éņŗż ņ×ģņøÉ, ņŗ¼ņןņĀĢņ¦Ć, ņé¼ļ¦ØņØä ņĪ░ņé¼Ē¢łļŗż. ļéśņØ┤ļīĆ ļČäļźś ĻĖ░ņżĆņØĆ ņśüņĢäĻĖ░ļŖö 1ņäĖ ļ»Ėļ¦ī, ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░ļŖö 1-5ņäĖ, ĒĢÖļĀ╣ĻĖ░ļŖö 6-11ņäĖ, ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ļŖö 12-18ņäĖļĪ£ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņĀĢņØśĒ¢łļŗż.

4. ĒåĄĻ│äņŚ░ņåŹĒśĢ ļ│ĆņłśļŖö ĒÅēĻĘĀ ļ░Å Ēæ£ņżĆĒÄĖņ░© ļśÉļŖö ņżæņĢÖĻ░Æ ļ░Å ņé¼ļČäņ£äņłś ļ▓öņ£äļĪ£, ļ▓öņŻ╝ĒśĢ ļ│ĆņłśļŖö ņłś ļ░Å ļ░▒ļČäņ£©ļĪ£ Ļ░üĻ░ü Ēæ£ņŗ£Ē¢łļŗż. ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł ļģĖņČ£ Ēøä ņ”Øņāü ļ░£ņāØĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņŗ£Ļ░äņØĆ ņĀĢĻĘ£ļČäĒżļź╝ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ Student t-testļź╝, ņ×äņāüņ”Øņāü, ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦ł, ņ╣śļŻīņØś ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│ä ņ░©ņØ┤ļŖö Fisher exact testļź╝ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņé¼ņÜ®Ē¢łļŗż. ļČäņäØņŚÉņä£ P < 0.05ļź╝ ĒåĄĻ│äņĀü ņ£ĀņØśņä▒ņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀĢņØśĒ¢łļŗż. ĒåĄĻ│äņĀü ļČäņäØņŚÉļŖö SPSS ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY)ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®Ē¢łļŗż.

Ļ▓░Ļ│╝Ēć┤ņŗżņ¦äļŗ© ĻĖ░ņżĆ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö 138ļ¬ģņ£╝ļĪ£, ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ĻĖ░Ļ░äņŚÉ ņØæĻĖēņŗżņØä ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ ņåīņĢäņ▓Łņåīļģä ĒÖśņ×É 36,245ļ¬ģņØś 0.4%ļź╝ ņ░©ņ¦ĆĒ¢łļŗż. ņŚ¼ĻĖ░ņä£ ņ×ÉĻ░ĆņŻ╝ņé¼ņÜ® ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ĻĘ╝ņ£Īļé┤ņŻ╝ņé¼ Ēøä ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ 3ļ¬ģ, ņÖĖļČĆ ļ│æņøÉņŚÉņä£ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢ£ ņĢĮ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ Ēøä ņØ┤ņåĪļÉ£ 6ļ¬ģ, ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ¦äļŗ© ĻĖ░ņżĆņØä ļ¦īņĪ▒ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö 21ļ¬ģņØä ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ 108ļ¬ģņØä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļīĆņāüņ×ÉļĪ£ ļČäņäØĒ¢łļŗż(Fig. 1). ņāüĻĖ░ 138ļ¬ģ ņżæ ņĢĮ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ Ēøä ņØæĻĖēņŗż ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ 9ļ¬ģņØä ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ 129ļ¬ģ ņżæ 108ļ¬ģņØ┤ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļĪ£ ņĄ£ņóģ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņ¢┤ ņĢäļŗłĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ¦äļŗ©ņØś ĒŖ╣ņØ┤ļÅäļŖö 83.7%ņśĆļŗż.

ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļīĆņāüņ×ÉņØś ļéśņØ┤ ņżæņĢÖĻ░ÆņØĆ 4ņäĖ(ņé¼ļČäņ£äņłś ļ▓öņ£ä, 2-14ņäĖ)ņśĆĻ│Ā, ļé©ņ×ÉļŖö 61ļ¬ģ(56.5%)ņØ┤ņŚłļŗż. ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│ä ļČäĒżļŖö ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░Ļ░Ć 55ļ¬ģ(50.9%)ņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łĻ│Ā, ĻĘĖ ņÖĖ ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░(34ļ¬ģ[31.5%]), ĒĢÖļĀ╣ĻĖ░(16ļ¬ģ[14.8%]), ņśüņĢäĻĖ░(3ļ¬ģ[2.8%]) ņł£ņØ┤ņŚłļŗż(Table 2). ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ ļ░Å ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż Ļ│╝Ļ▒░ļĀźņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö Ļ░üĻ░ü 81ļ¬ģ(75.0%) ļ░Å 7ļ¬ģ(6.5%)ņØ┤ņŚłļŗż.

ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦łļĪ£ļŖö ņŗØĒÆłņØ┤ 80ļ¬ģ(74.1%)ņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░Ćņן ļ¦ÄņĢśĻ│Ā, ĻĘĖ ņÖĖ ņĢĮ 11ļ¬ģ(10.2%), ņŗØĒÆł ņŚ░Ļ┤Ć ņÜ┤ļÅÖ ņ£Āļ░£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż(food-associated, exercise-induced anaphylaxis, FAEIA) 3ļ¬ģ(2.8%), Ļ░ĢņĢäņ¦ĆĒäĖ 1ļ¬ģ(0.9%), ņøÉņØĖ ļ»ĖņāüņØ┤ 13ļ¬ģ(12.0%)ņØ┤ņŚłļŗż(Table 2). ļģĖņČ£ Ēøä ņ”Øņāü ļ░£ņāØĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņŗ£Ļ░äņØĆ ņØīņŗØņØ┤ 1.5 ┬▒ 1.4ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ņŚłĻ│Ā ņĢĮņØĆ 1.6 ┬▒ 1.4ņŗ£Ļ░äņ£╝ļĪ£, ņØīņŗØĻ│╝ ņĢĮļ¼╝ņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ļæÉ ĻĄ░ Ļ░äņŚÉ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ£ ņ░©ņØ┤ļŖö ņŚåņŚłļŗż. ļ¬©ļōĀ ļéśņØ┤ļīĆņŚÉņä£ ņØīņŗØņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łĻ│Ā ļéśņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢĀņłśļĪØ ņĢĮ ļ░Å ņøÉņØĖ ļ»ĖņāüņØś ļ╣łļÅäĻ░Ć ļŖśņ¢┤ļé¼ļŗż(Fig. 2). ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņśüņĢäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×É 3ļ¬ģ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņØīņŗØ ļģĖņČ£ Ēøä ļ░£ņāØĒ¢łĻ│Ā, ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×É ņżæ ņØīņŗØ 52ļ¬ģ(94.5%), ņĢĮ, Ļ░ĢņĢäņ¦ĆĒäĖ, ņøÉņØĖ ļ»ĖņāüņØ┤ Ļ░ü 1ļ¬ģ(1.8%)ņØ┤ņŚłļŗż. ĻĖ░ĒāĆ ļéśņØ┤ļīĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņØīņŗØņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĒĢÖļĀ╣ĻĖ░ 9ļ¬ģ(56.3%), ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ 16ļ¬ģ(47.1%)ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļ®┤ņä£ ĻĘĖ ļ╣łļÅäļŖö ņĀÉņ░© Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż.

ņ×äņāüņ”ØņāüņØĆ Ēö╝ļČĆņ”ØņāüņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łĻ│Ā(105ļ¬ģ[97.2%]), ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│ä ņ”Øņāü 97ļ¬ģ(89.8%), ņ£äņןĻ┤Ć ņ”Øņāü 31ļ¬ģ(28.7%), ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”Øņāü 11ļ¬ģ(10.2%) ņł£ņØ┤ņŚłļŗż(Table 3). ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│äļĪ£ ļ¬©ļōĀ ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ Ēö╝ļČĆņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņśĆĻ│Ā, ļ¬©ļōĀ ĒĢÖļĀ╣ĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż. ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØĆ ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ņŚÉņä£ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łĻ│Ā, ņ£ĀņØ╝ĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ£ ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│ä ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņŚłļŗż(P = 0.002).

ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżņØś ņ╣śļŻīļŖö ĒĢŁĒ׳ņŖżĒāĆļ»╝ņĀ£ļź╝ Ļ░Ćņן ņ×ÉņŻ╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ē¢łĻ│Ā(105ļ¬ģ[97.2%]), ĒŖ╣Ē׳ Ēö╝ļČĆņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ļéśĒāĆļé£ ļ¬©ļōĀ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ē¢łļŗż. ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ĻĘ╝ņ£Īļé┤ņŻ╝ņé¼ļŖö 82ļ¬ģ(75.9%)ņŚÉĻ▓ī Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ē¢łņ£╝ļ®░, ļéśņØ┤ņÖĆ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņśĆņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ļŖö ĒåĄĻ│äņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ£ ņ░©ņØ┤ļź╝ ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż(P = 0.037) (Table 4). ņĀĢļ¦źļé┤ ņłśņĢĪņÜöļ▓ĢļÅä ņØ┤ņÖĆ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż. ĒĢŁĒ׳ņŖżĒāĆļ»╝ņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ 3ļ¬ģ ļ¬©ļæÉ Ēö╝ļČĆņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśĻ│Ā, ņŖżĒģīļĪ£ņØ┤ļō£ļź╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ 15ļ¬ģ ņżæ 12ļ¬ģņØĆ ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż. ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØĖ 11ļ¬ģ ļ¬©ļæÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ē¢łļŗż. ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢ£ 82ļ¬ģ ņżæ ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØĆ 73ļ¬ģņŚÉņä£, ņ£äņןĻ┤Ć ņ”ØņāüņØĆ 25ļ¬ģņŚÉņä£, Ļ░üĻ░ü ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż. ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ 26ļ¬ģ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ ņżæ 17ļ¬ģņØĆ ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│żļ×ĆņØä ĒśĖņåīĒ¢łņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņé░ņåīĒżĒÖöļÅä Ļ░Éņåī, ņīĢņīĢĻ▒░ļ”╝ ļśÉļŖö Ēśæņ░®ņØīņØä ļÅÖļ░śĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśĻ│Ā, ļéśļ©Ėņ¦Ć 9ļ¬ģņØĆ ļ│ĄĒåĄņØĆ ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ĻĄ¼ņŚŁ, ĻĄ¼ĒåĀ, ņäżņé¼ ļō▒ņØä ļÅÖļ░śĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż.

ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņ×ģņøÉ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö 4ļ¬ģ(3.7%)ņØ┤ņŚłĻ│Ā, ļ¬©ļæÉ ņĪ░ĻĖ░ņŚÉ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ē¢łņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ņ¦ĆņåŹĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ×ģņøÉ ņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ļ░øņĢśļŗż. ņØ┤ 4ļ¬ģņØś ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĆ ļĢģņĮ®, ļ®öļ░Ć, ņāłņÜ░, ĒĢŁņāØņĀ£Ļ░Ć Ļ░ü 1ļ¬ģņØ┤ņŚłĻ│Ā, ļ¬©ļæÉ ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”Ø ņŚåņØ┤ Ēć┤ņøÉĒ¢łļŗż. ņżæĒÖśņ×Éņŗż ņ×ģņøÉ ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØņØĆ ņŚåņŚłļŗż.

Ļ│Āņ░░ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ņśüņĢäĻĖ░ ļ░Å ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”Øņāü ļ░Å ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ╣łļÅäĻ░Ć ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ļ│┤ļŗż ļé«ņØīņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņżĆļŗż. ņĀäņ×ÉņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņØĆ ĻĖ░ļÅäĒÅÉņćä ļ░Å ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│żļ×ĆņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņāØļ”¼ņĀü ļ│┤ņāüļŖźļĀźņØ┤ ļ¢©ņ¢┤ņ¦ĆļŖö ļ░śļ®┤, ĒśłņĢĢ ņĀĆĒĢśņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņ╣┤ĒģīņĮ£ņĢäļ»╝ ļČäļ╣äļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ£ ļ│┤ņāüļŖźļĀźņØ┤ ņÜ░ņłśĒĢśņŚ¼ ņć╝Ēü¼Ļ░Ć ļŖ”Ļ▓ī ļ░£Ļ▓¼ļÉśĻĖ░ ņēĮļŗż[11]. ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä ļŖ”Ļ▓ī Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśļ®┤ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ¦ĆņŚ░ ļ░śņØæņØ┤ ļŹö ĒØöĒĢśĻ│Ā ņŗ¼ĒĢśĻ▓ī ņØ╝ņ¢┤ļé£ļŗż[12]. ļśÉĒĢ£, ņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņśüņĢäĻĖ░ ļ░Å ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņŻ╝ļÉ£ ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØĖ ņØīņŗØņŚÉ ļģĖņČ£ Ēøä ĻĖēņä▒ ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│żļ×Ć ļ░Å ņĀÉļ¦ēĒö╝ļČĆņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļ®┤ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ņŚåņØ┤ļÅä ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļĪ£ Ļ░äņŻ╝ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä ņĀüĻĘ╣ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢ£ļŗż[13,14].

ņ”ØņāüņØä ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│äļĪ£ ĻĄ¼ļČäĒĢśņŚ¼ ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņĀä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ļČĆņĪ▒ĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ¢┤ļĀĄņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ļ¬©ļōĀ ļéśņØ┤ļīĆņŚÉņä£ Ēö╝ļČĆņ”ØņāüņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łļŹś ņĀÉņØĆ ņØ┤ņĀä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņÖĆ ņØ╝ņ╣śĒĢ£ļŗż[7-10]. ņåīņĢä ļ░Å ņä▒ņØĖņØś ņ”ØņāüņØä ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉ ļö░ļź┤ļ®┤, ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ņä▒ņØĖņŚÉņä£ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ļŹö ĒØöĒ¢łĻ│Ā, ņ£äņןĻ┤Ć ņ”ØņāüņØĆ ņåīņĢäņŚÉņä£ ĒØöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņśĆņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ£ ņ░©ņØ┤ļŖö ņŚåņŚłļŗż[9]. ņØ┤ļŖö ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ņŚÉņä£ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒ¢łļŹś ņĀÉ ļ░Å ļéśņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņ£äņןĻ┤Ć ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņØĖ ņĀÉĻ│╝ ņØ╝ņ╣śĒĢ£ļŗż. ņ£Āļ░£ ņøÉņØĖņØĆ ļ¬©ļōĀ ļéśņØ┤ļīĆņŚÉņä£ ņØīņŗØņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒĢ£ ņ£Āļ░£ ņČöņĀĢ ņøÉņØĖ ļ¼╝ņ¦łņØ┤ņŚłĻ│Ā ņä▒ņØĖņŚÉņä£ ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢĮņØś ļ╣łļÅäĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒ¢łļŖöļŹ░[8,9], ņØ┤ļŖö ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ļéśņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņØīņŗØ ļ╣łļÅäļŖö Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśĻ│Ā(P = 0.001) ņĢĮņØś ļ╣łļÅäļŖö ņ”ØĻ░Ć(P = 0.011)ĒĢ£ ņĀÉĻ│╝ ņØ╝ņ╣śĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ļ░£ņāØļźĀņØĆ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö ņČöņäĖļĪ£, ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ Ļ▒┤Ļ░Ģļ│┤ĒŚśņŗ¼ņé¼ĒÅēĻ░ĆņøÉ ņ×ÉļŻīļź╝ ļČäņäØĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉ ļö░ļź┤ļ®┤, ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×ÉĻ░Ć 2010ļģäņØś 0.02%ņÖĆ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņŚ¼ 2014ļģäņŚÉļŖö 0.04%ļĪ£ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒ¢łļŗż[15]. ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņØæĻĖēņŗż ĒÖśņ×É ņżæ 0.3%Ļ░Ć Ēć┤ņøÉ ņŗ£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļĪ£ ņ¦äļŗ©ļÉÉļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ ņĪ░ĻĖ░ ņ¦äļŗ© ļ░Å ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ļ░Ć ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ļŹ░, ņ¦äļŗ© ļ░Å ņ╣śļŻīĻ░Ć ļŖ”ņ¢┤ņ¦Ćļ®┤ ņ×ģņøÉ ļ╣łļÅäĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśĻ│Ā ļō£ļ¼╝Ļ▓ī ņé¼ļ¦ØņØä ņ┤łļלĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[5,6]. ņśüĻĄŁņŚÉņä£ 10ļģäĻ░ä 202ļ¬ģņØ┤[16], ĒśĖņŻ╝ņŚÉņä£ļŖö 9ļģäĻ░ä 112ļ¬ģ[17]ņØ┤ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņé¼ļ¦ØĒ¢łļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒ¢łņ£╝ļ®░, ĒĢ£ĻĄŁņŚÉņä£ļÅä 2001-2004ļģäņŚÉ 5ļ¬ģņØ┤ ņé¼ļ¦ØĒ¢łļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒ¢łļŗż[18]. ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ļ¦Ø ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņŚåņŚłņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņ×ģņøÉ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö 4ļ¬ģņØ┤ņŚłļŗż. ĒĢ£ĻĄŁņØś ņĀäņ▓┤ ļéśņØ┤ ĒÖśņ×É ļīĆņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņ×ģņøÉņØĆ 91ļ¬ģ ņżæ 6ļ¬ģņØ┤ņŚłĻ│Ā ņżæĒÖśņ×Éņŗż ņ×ģņøÉ ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØņØĆ ņŚåņŚłņ£╝ļ®░[9], ņśüĻĄŁ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ļ░£ņāØ ļ░Å ņ×ģņøÉņØĆ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņé¼ļ¦ØņŚÉļŖö Ēü░ ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņŚåļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒ¢łļŗż[19].

ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņĪ░ĻĖ░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ļ¦ØĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņŗ¼Ļ░üĒĢ£ ņśłĒøäļź╝ ņśłļ░®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż[5,6,20]. ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØ┤ ņØ╝ņ░© ņäĀĒāØ ņĢĮņĀ£ņØ┤ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņØśļŻīņ¦äņØ┤ ņ”ØņāüņØä Ļ░äĻ│╝ĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ļČĆņ×æņÜ®ņØä ņÜ░ļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ļź╝ ņŻ╝ņĀĆĒĢśĻĖ░ļÅä ĒĢ£ļŗż[21,22]. ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ¦äļŗ©ņØĆ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņé¼ļ¦ØņØĆ ļō£ļ¼╝ņ¢┤ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ņĀüņØĆ Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤Ļ│Ā[23], ņŗżņĀ£ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ╣łļÅäņØś ļéśņØ┤ļīĆ ļ░Å ņ¦ĆņŚŁ ļ│ä ĒÄĖņ░©Ļ░Ć ņŗ¼ĒĢśļŗż[4,24-26]. ĒĢ£ĻĄŁņŚÉņä£ 5ļģäĻ░ä ņĀäņ▓┤ ļéśņØ┤ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▒┤Ļ░Ģļ│┤ĒŚśņŗ¼ņé¼ĒÅēĻ░ĆņøÉ ņ×ÉļŻī ļČäņäØ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉ ļö░ļź┤ļ®┤, ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØ┤ ņĀäņ▓┤ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś 35.8%ņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉÉļŗż[4]. ļ»ĖĻĄŁņŚÉņä£ļŖö 1ļģäĻ░ä ņØæĻĖēņŗżņØä ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņåīņĢäĒÖśņ×ÉņØś 48%ņŚÉņä£[24], ņŗ▒Ļ░ĆĒżļź┤ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņØæĻĖēņŗżņØä ļ░®ļ¼ĖĒĢ£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņåīņĢäĒÖśņ×ÉņØś 86.6%ņŚÉņä£ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉÉļŗż[25]. ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā ņåīņĢä ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņä▒ņØĖļ│┤ļŗż ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ╣łļÅäĻ░Ć ļé«ļŗżļŖö ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÅä ņ׳ļŗż[26]. ĒĢŁĒ׳ņŖżĒāĆļ»╝ņĀ£ ļ░Å ņŖżĒģīļĪ£ņØ┤ļō£Ļ░Ć ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä ļīĆņ▓┤ĒĢĀ ņłś ņŚåņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£, ņØæĻĖēņŗż ņØśļŻīņ¦äņŚÉĻ▓ī ņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņ¦äļŻīĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻĄÉņ£ĪĒĢ©ņ£╝ļĪ£ņŹ© ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ╣łļÅäļź╝ ņĀ£Ļ│ĀĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[19,27,28]. ļśÉĒĢ£, ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ĻĘ╝ņ£Īļé┤ņŻ╝ņé¼ļŖö ļČĆņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ļō£ļ¼╝ņ¢┤, ļŹö ņĀüĻĘ╣ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢ£ļŗż[2,20,21]. ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØ┤ ņĀäņ▓┤ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļīĆņāüņ×ÉņØś 75.9%ņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśņ¢┤ ņØ┤ņĀä ļ│┤Ļ│Āļ│┤ļŗż ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ļåÆņĢśļŗż. Ē¢źĒøä ņĀĢĻĖ░ņĀüņØĖ ņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣© ĻĄÉņ£Ī ļ░Å ņ×äņāüņ¦äļŻīņ▓┤Ļ│ä(clinical pathway) ĻĄ¼ņČĢņØä ĒåĄĒĢ┤, ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØä ļŖśļ”┤ ņłś ņ׳ņØä Ļ▓āņØ┤ļŗż.

ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ļ░Å ņĀĢļ¦źļé┤ ņłśņĢĪņÜöļ▓Ģ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ļéśņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļ│┤ņØĖ Ļ▓āņØĆ ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ĒØöĒĢ£ Ļ▓āĻ│╝ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņČöņĀĢĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ╣śļŻīņØś ļéśņØ┤ļīĆļ│ä ņ░©ņØ┤ņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļČĆņĪ▒ĒĢ£ ņŗżņĀĢņØ┤ļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£, ņןĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ņ¢┤ļ”░ ņåīņĢäņŚÉņä£ ļé«ņØĆ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”Øņāü ļ░Å ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ╣łļÅäņØś ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆņØä ņ×ģņ”ØĒĢĀ ĒĢäņÜöĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż.

ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀÉņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ļŗ©ņØ╝ ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ć ĒøäĒ¢źņĀü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØĖ ņĀÉĻ│╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņ¦¦ņØĆ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļīĆņāüņ×ÉĻ░Ć ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņĀüņŚłļŹś ņĀÉņØä ļōż ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, Ēć┤ņŗż ĒĢ£ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼, ļŗżļźĖ ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ņ¦äļŗ©ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņלļ¬╗ ņ¦äļŗ©ļÉ£ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢśņ¦Ć ļ¬╗Ē¢łļŗż. Ē¢źĒøä ļŗżļźĖ ņĢīļĀłļź┤ĻĖ░ Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ņ¦äļŗ©ļ¬ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒżĒĢ©ĻĖ░ņżĆņØä ĒÖĢļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ņ£äņØīņä▒ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņןĻĖ░Ļ░ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż.

ņÜöņĢĮĒĢśļ®┤, ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖż ĒÖśņ×É ņżæ ņśüņĢäĻĖ░ ļ░Å ĒĢÖļĀ╣ņĀäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņ▓ŁņåīļģäĻĖ░ ĒÖśņ×Éļ│┤ļŗż ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”Øņāü ļ░Å ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ╣łļÅäĻ░Ć ļé«ņĢśļŗż. ņĀäņ×ÉņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ ņŚåļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ņĢäļéśĒĢäļØĮņŗ£ņŖżļĪ£ ņØĖņ¦ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņĀüĻĘ╣ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŚÉĒö╝ļäżĒöäļ”░ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

Fig.┬Ā2.Triggers that caused pediatric anaphylaxis by age-group. FAEIA: food-associated, exercise-induced anaphylaxis.

Table┬Ā1.Clinical criteria for diagnosing anaphylaxis [14] Table┬Ā2.Characteristics of the study population Table┬Ā3.Age group characteristics of clinical features and triggers in the children

Table┬Ā4.Initial treatments at the emergency department References1. Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, Adkinson NF Jr, Bock SA, Branum A, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report. Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:391ŌĆō7.

2. Anagnostou K, Turner PJ. Myths, facts and controversies in the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:83ŌĆō90.

3. Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Bilo MB, El-Gamal YM, Ledford DK, Ring J, et al. World allergy organization guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J 2011;4:13ŌĆō37.

4. Jung WS, Kim SH, Lee H. Missed diagnosis of anaphylaxis in patients with pediatric urticaria in emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2018;Oct 2; [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001617.

5. Hochstadter E, Clarke A, De Schryver S, LaVieille S, Alizadehfar R, Joseph L, et al. Increasing visits for anaphylaxis and the benefits of early epinephrine administration: a 4-year study at a pediatric emergency department in Montreal, Canada. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137:1888ŌĆō90. e4.

6. Fleming JT, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr, Rudders SA. Early treatment of food-induced anaphylaxis with epinephrine is associated with a lower risk of hospitalization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:57ŌĆō62.

7. Rudders SA, Banerji A, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Age-related differences in the clinical presentation of food-induced anaphylaxis. J Pediatr 2011;158:326ŌĆō8.

8. Kim MJ, Choi GS, Um SJ, Sung JM, Shin YS, Park HJ, et al. Anaphylaxis: 10 years' experience at a university hospital in Suwon. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;28:298ŌĆō304. Korean.

9. Park HM, Noh JC, Park JH, Won YK, Hwang SH, Kim JY, et al. Clinical features of patients with anaphylaxis at a single hospital. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis 2012;22:232ŌĆō8. Korean.

10. Hong KR, Moon HJ, Lyu JW, Lee SY, Lee JS, Lee SH, et al. Clinical and statistical analysis of patients with anaphylaxis visiting the emergency room of a tertiary hospital. Korean J Dermatol 2019;57:126ŌĆō35. Korean.

11. American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma. Advanced trauma life support for doctors, student course manual 10th ed. Chicago (IL): American College of Surgeons: 2018. p. 195.

13. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association. Pediatric advanced life support: provider manual Dallas (TX): American Heart Association: 2016. p. 134.

14. Campbell RL, Li JT, Nicklas RA, Sadosty AT, Members of the Joint Task Force, Practice Parameter Workgroup. Emergency department diagnosis and treatment of anaphylaxis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;113:599ŌĆō608.

15. Jeong K, Lee JD, Kang DR, Lee S. A population-based epidemiological study of anaphylaxis using national big data in Korea: trends in age-specific prevalence and epinephrine use in 2010-2014. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2018;14:31.

16. Pumphrey R. Anaphylaxis: can we tell who is at risk of a fatal reaction? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;4:285ŌĆō90.

17. Liew WK, Williamson E, Tang ML. Anaphylaxis fatalities and admissions in Australia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:434ŌĆō42.

18. Lim DH. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Korean children. Korean J Pediatr 2008;51:351ŌĆō4. Korean.

19. Turner PJ, Gowland MH, Sharma V, Ierodiakonou D, Harper N, Garcez T, et al. Increase in anaphylaxis-related hospitalizations but no increase in fatalities: an analysis of United Kingdom national anaphylaxis data, 1992-2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:956ŌĆō63. e1.

20. Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1144ŌĆō50.

21. Prince BT, Mikhail I, Stukus DR. Underuse of epinephrine for the treatment of anaphylaxis: missed opportunities. J Asthma Allergy 2018;11:143ŌĆō51.

22. Chooniedass R, Temple B, Becker A. Epinephrine use for anaphylaxis: too seldom, too late: current practices and guidelines in health care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;119:108ŌĆō10.

23. Tejedor Alonso MA, Moro Moro M, Mugica Garcia MV. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:1027ŌĆō39.

24. Hemler JA, Sharma HP. Management of children with anaphylaxis in an urban emergency department. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;118:381ŌĆō3.

25. Ganapathy S, Lwin Z, Ting DH, Goh LS, Chong SL. Anaphylaxis in children: experience of 485 episodes in 1,272,482 patient attendances at a tertiary paediatric emergency department from 2007 to 2014. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2016;45:542ŌĆō8.

26. Choi YJ, Kim J, Jung JY, Kwon H, Park JW. Underuse of epinephrine for pediatric anaphylaxis victims in the emergency department: a population-based study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019;11:529ŌĆō37.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|